IMF, India, and a Rs 7.5 Cr Book Deal: Behind the Dismissal of K Subramanian

This kind of termination has not happened in the history of India’s 80 years of IMF membership, writes Subhash Garg.

advertisement

In an unprecedented move, the Government of India on 30 April ‘terminated’ the services of Krishnamurthy Subramanian, India’s Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), ‘with immediate effect.’

To the best of my knowledge, this kind of termination has never happened in the history of India’s 80 years of ownership and membership of the World Bank and the IMF.

For India, too, the episode has left many scars. India’s seat on the IMF board fell ‘vacant’ with immediate effect, making the alternate ED from Sri Lanka the de facto ED of the Indian constituency in the IMF. The government had to designate Parmeswaran Iyer, India’s ED at the World Bank, as a temporary ED in the IMF for an Indian to cast the very important vote on the IMF’s $1.3 billion programme for Pakistan coming up for approval in IMF Board on 9 May. There is also tremendous reputation loss.

A Managed Appointment as CEA

A Selection Committee—headed by former RBI governor Bimal Jalan, the then DoPT secretary C Chandramouli, and me, as Secretary of the Department of Economic Affairs (DEA)—interviewed Subramanian for the Chief Economic Advisor (CEA)'s role in 2018. The committee did not find him adequately qualified for the job.

The zone of consideration was expanded by inviting some more economists for interviews. The current CEA, V Anantha Nageswaran, was found to be the most suitable. The committee placed Nageswaran at number one and included Subramanian’s name at number two, more as a contingency.

Nageswaran at that time was a Singaporean citizen. We scrutinised the rules, which permitted a foreign national to be appointed as CEA. As Nageswaran was a person of Indian origin and had worked almost entirely on India, the DEA processed his case for appointment. We were completely convinced that Nageswaran would be appointed CEA by the Appointment Committee of Cabinet (ACC).

In the six months I spent with him as CEA, I found him highly ambitious and opportunistic—always working to endear him in the eyes and ears of powers that be—but quite superficial and impulsive. I did not allow his half-baked ideas much space in economic policymaking.

We drifted apart. By the time the regular Budget was presented in July 2019, he had become quite antagonistic. It did not matter to me.

Reached IMF Singing Paeans

Subramanian is primarily borne on the rolls of the International School of Business, Hyderabad. For reasons unknown to me, his term as CEA was not extended in 2021. From his public appearances at that time, it was clear that there must have been some disenchantment. Nageswaran was appointed CEA in his place, three years later than we had recommended.

Within about a year, it appears he managed to repair his relationship with the government and bounced back as India’s ED at the IMF. In his two and half years at the IMF, Subramanian appeared in countless media interactions, business channels and otherwise, speaking for the government. He would always speak of how great the Modi government has been, and what great future the Modi government been building for India.

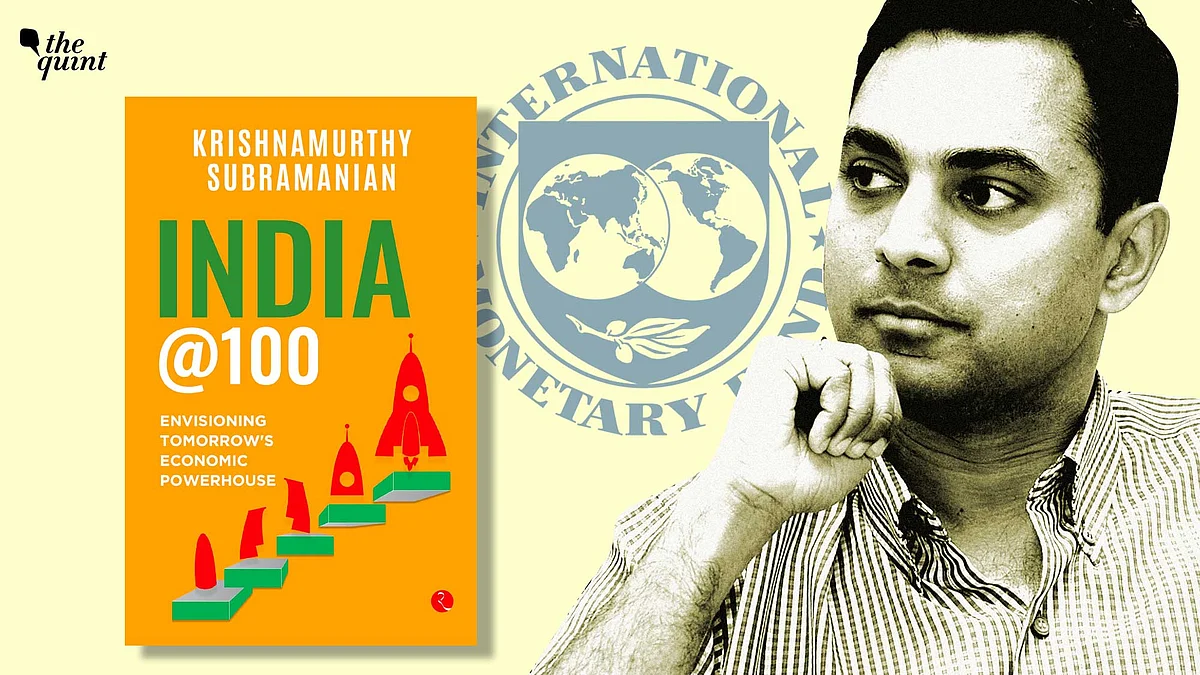

His book India @100: Envisioning Tomorrow’s Economic Powerhouse is also a paean of to Modi’s policies, built around four pillars, and how India is racing ahead to be $55 trillion economy by 2047. If you read it thoroughly and critically, its emptiness and rhetoric become apparent.

He frequently returned to India to present the book to the high and mighty, and promoting it through book release functions, which every industry house and organisation in India was persuaded or forced to organise.

What Led to the Ignominious Termination?

The Government of India has not mentioned any specific reason in the termination order.

Prime Minister Modi must have seen the evidence of his gross misdemeanour before being persuaded to sack him, with all the attendant consequences and bad publicity.

What might his misdemeanors be?

The sack does not be entirely at the initiative of Government of India. The Union Bank of India purchase scandal took place in December 2024. The General Manager, who ordered the mass-purchase of Subramanian's books, was placed under suspension in December/January, more than four months back.

As Union Bank of India is a public sector bank, the report must have reached the government much earlier. Subramanian would have known it all as well. He was confident about managing the situation. He was going about his business as if nothing unusual had happened. He was due to appear in a media event in New York on 1 May as well.

My sense is, though I don’t know the facts, that the Union Bank matter of book purchase must have reached IMF’s Ethics Committee, which reviews misconduct by EDs.

There could have also been a case of use or misuse of the IMF’s funds in paying for his visits to India for promotion of his book, including purchasing some. In addition, there is reportedly a case of use/misuse of the IMF’s confidential data or system in an unauthorised manner to promote India story or his book.

What Next for Subramanian?

More skeletons may yet emerge from Subramanian’s and the IMF’s closets in the days to come. Subramanian will have to, unless he has already, return to India as soon as possible.

He will most likely report back to ISB. Will ISB accept him as if nothing has happened, or will it initiate action against him for his misconduct? Most likely, it will be the latter.

Even students at ISB may now hesitate to see Subramanian as a role model.

The wilderness awaits him.

(Subhash Chandra Garg is the Chief Policy Advisor, SUBHANJALI, and Former Finance and Economic Affairs Secretary, Government of India. He's the author of many books, including 'The $10 Trillion Dream Dented, 'We Also Make Policy', and 'Explanation and Commentary on Budget 2025-26'. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined