India–UK Trade Deal Sets the Stage for a New Global Alignment

The India-UK FTA seeks to benefit the partners at the expense of existing suppliers, writes Sanjeev Ahluwalia.

advertisement

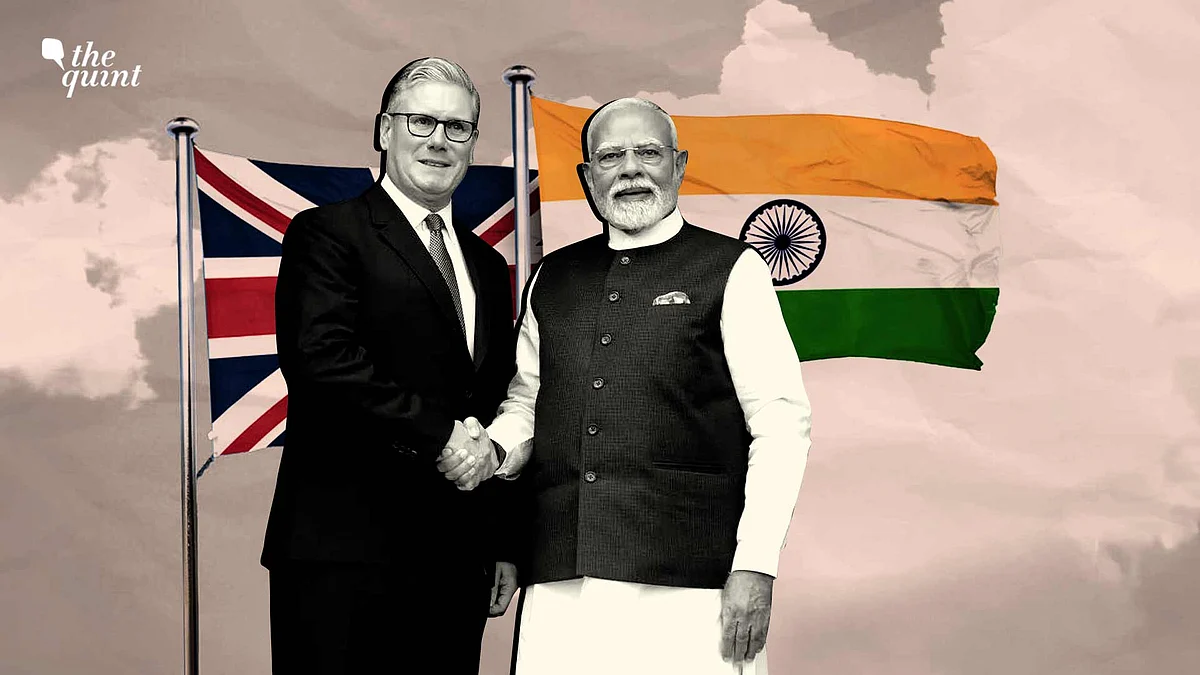

Perhaps it was the bonhomie induced by a balmy summer day in London, or sheer ennui after a three-year long negotiation or more likely canny logic, which brought the cousins together on 24 July for the signing of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and a UK-India Trade Vision statement for 2035.

The relationship began with trade 400 years ago, so it is fitting that the first large UK trade deal—after its ill-advised exit from the European Union (EU) in 2020—should be with India.

Its 1.4 billion youthful demographics added $1.87 trillion in current terms to domestic purchasing power between 2014 and 2024 (current prices added) compared to the UK's $0.58 trillion. A set of shared languages—English, Hindi, Gujarati, and Punjabi—add further glue to this historic relationship.

When Similar Strengths Limit Trade

At the signing ceremony, an interpreter struggled to translate UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s conversational English into chaste Hindi, prompting Prime Minister Narendra Modi to remark, "Don’t worry, please use English words if they are tough to translate." This underscored the linguistic bridges already in place between the two countries.

Trade thrives on complementarities, not similarities in economic strengths. Unsurprisingly, neither the UK nor India are in the top ten importing or exporting countries for each other. This is also because the UK remains tightly integrated with the US, the EU, and China, with which, like India, it has the largest trade deficit.

Government Procurement and Auto Sector Access

Given the paucity of instant complementarities, the FTA seeks to benefit the partners at the expense of existing suppliers. UK suppliers will now be able to compete for government business in India except where value limits reserve contracts for India’s MSME (micro, small and medium enterprises).

Total purchases by the Union, state, and local governments are about $400 billion annually, projected to grow at around 10 to 11 percent each year in current rupee terms.

Automotive manufacturing is a flagship domestic sector with significant ancillary suppliers, employing 40 million people directly or indirectly. Expect to see more Rolls Royce and Aston Martin cars on the roads, along with SUVs from the TATA-owned Jaguar Land Rover.

Lower import tariffs will put the onus on industrial policy to enhance domestic industry competitiveness via energy pricing reforms, lower logistical cost, tax rationalisation, lowering the regulatory cost for business, and simplification of arbitration and judicial review processes, to retain the incentive for manufacturing automobiles in India rather than flooding the market with imports.

Enforcement of adequate minimum value addition norms in engineering imports can avoid proxy exports and dumping of goods.

Whisky, Gin, Cosmetics: A Taste for Imports

Tipplers in India would welcome that import duties on British whisky and gin will fall from 50 percent to 40 percent over a decade. This is fitting. The plucky, domestic premium whisky industry—brands like Amrut, Indri, Rampur, Kamet, Woodburns, and Paul Johns—are already available in UK retailers, bars, and private collections.

Producers in agriculture and dairy can rest easy since no concessions have been given for imports in these sensitive segments. Producers in India’s traditional export manufactures such as textiles, leather goods, and footwear, will get access to the UK market at zero import duty—enhancing their export potential significantly versus regional rivals.

In return, UK exports in telecom, construction, and environmental services have been facilitated without compulsorily having a local office. UK banks and insurance companies will be treated on par with Indian business counterparts, though the door for legal services is yet to be opened.

What’s Protected, What’s Gained

This deal sets the tone for India’s FTAs with the US and the EU, with four clear messages to frame the ongoing discussions.

Concessions on agriculture are not negotiable. This is a pity since genetically modified seeds enhance productivity, which along with rationalisation of fiscal outlays away from production linked subsidies, remains captive to political economy constraints.

India’s automotive industry is now assessed to be globally competitive and must prepare for disruptive innovation by imports or incentivised foreign investment for manufacture in India.

A healthy principal has been established that import concessions for India’s traditional, worker-intensive, export products can be traded for partial access to imports for government purchases in India.

India can consider equitably, and proportionately, phasing in global social and environmental principles into trade.

Finally, the FTA sends an implicit message that India’s response to drop-dead deadlines will be to keep talking amiably, till both sides have proportionate skin in the game.

(Sanjeev Ahluwalia is a distinguished fellow at the Chintan Research Foundation and was previously in the IAS and World Bank. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined