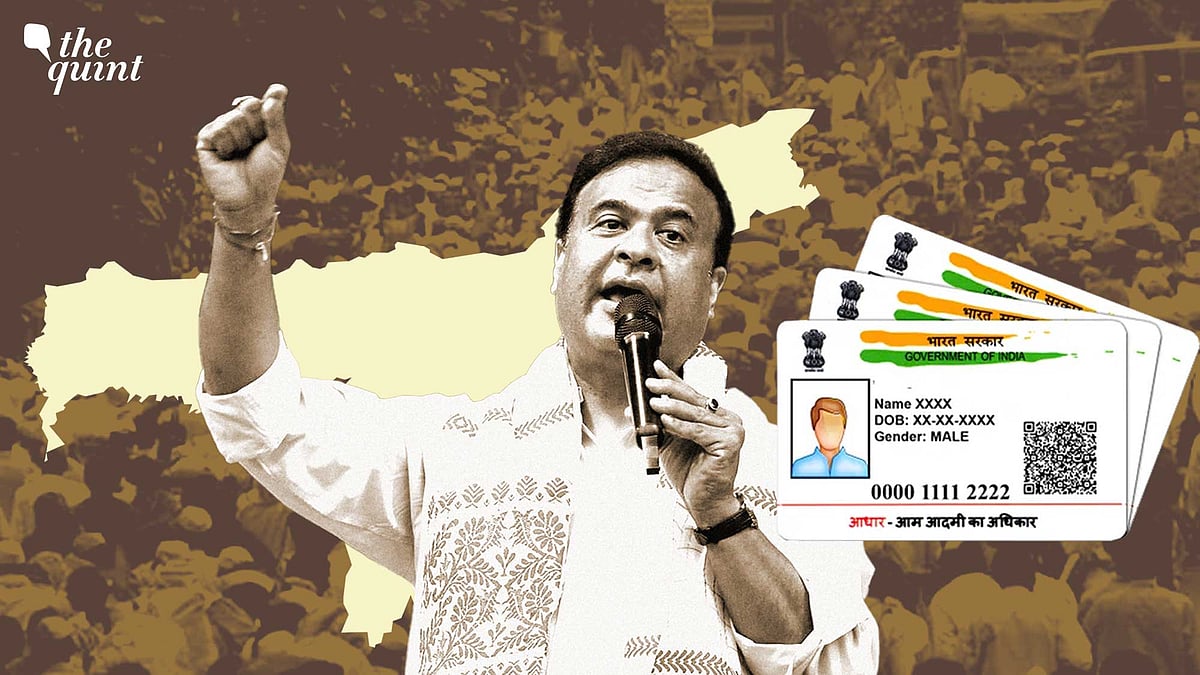

Assam’s Aadhaar Curb: Politics Masquerading as Law Won't Stand Judicial Scrutiny

The Aadhaar Act of 2016 clearly leaves no room for such state-level diktats, writes Sanjay Hegde.

advertisement

In a controversial move, the BJP-led Assam Cabinet helmed by Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has declared that October 2025 onwards, no new adults will be issued an Aadhaar card. Individuals from the Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, and tea garden workers are exempt from this rule for a year.

Coming as it is in the larger backdrop of evictions, detentions and deportations of Bengali-speaking Muslims in particular in Assam, the pronouncement is clearly political theatre, not law.

The Aadhaar Act of 2016 clearly leaves no room for such state-level diktats.

Section 3(1) gives every resident of India the right to obtain an Aadhaar. A “resident” is defined as someone who has lived in India for 182 days in the preceding year. Citizenship is not the test, and neither is age beyond the requirement of being alive and present.

The Chief Minister of a state has no locus under this Act to deny enrolment. Aadhaar is administered by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), a statutory body under the Parliament. States may help as registrars, but they cannot curtail what Parliament has guaranteed. If any official were to actually follow such a directive, constitutional courts would be bound to intervene.

Aadhaar Was Never About Citizenship

The justification offered is that Aadhaar could be misused by foreigners to claim citizenship. But the Act itself forecloses that claim. Section 9 spells it out: Aadhaar neither confers nor proves citizenship. It is proof of residence, not nationality.

To wield Aadhaar as a tool to police citizenship is to misuse it. It is as though one tried to decide voting rights on the basis of a ration card. The wrong tool for the wrong purpose.

But who pays the price?

Imagine the teenager in Dibrugarh who was never enrolled as a child because her parents missed the paperwork. At 18, she suddenly finds the door closed. Without Aadhaar she cannot sit for competitive exams, apply for scholarships, or even open a bank account. She has broken no law, yet she is punished by the law’s misapplication.

This is exclusion masquerading as protection. It strikes at precisely the people Aadhaar was designed to include.

The Constitutional Problem

The Constitution does not permit such arbitrariness and contains safeguards for the following:

● Equality (Article 14): Treating 17-year-olds and 18-year-olds differently with no rational basis is discrimination.

● Dignity (Article 21): Aadhaar has become the gateway to rations, pensions, healthcare, and education. To deny it is to deny dignity itself.

● Freedom of movement (Article 19): Migrant workers entering Assam need Aadhaar for services. This measure would hobble them unlawfully.

The Supreme Court, in Puttaswamy (2017), upheld Aadhaar’s constitutionality only on the condition of proportionality. Assam’s approach is the antithesis of proportionality—a blunt hammer that smashes rights rather than tailoring restrictions.

The Case of Bihar

Why then make such an announcement? The answer may lie in timing. The Supreme Court recently directed the use of Aadhaar in the Bihar Special Revision (SIR) case, underscoring its role in transparency and inclusion. Aadhaar is now inescapable.

Assam faces elections soon. A measure that denies new Aadhaar enrolments above 18 has the predictable effect of shrinking the rolls of fresh voters—many of whom may not be politically convenient to the ruling party. The fear of infiltration is the fig leaf; the exclusion of voters is the real objective.

Aadhaar was supposed to be different: a tool of inclusion, not exclusion. Yet here we are again, with a policy that would deny people their identity at the very moment they come of age.

Remedy Worse Than the Disease

Fraud in enrolment is a concern. But the Act already provides safeguards: verification requirements, penalties for impersonation, and audits. The remedy is to strengthen these safeguards, not to slam the door on every adult.

Governance cannot mean punishing everyone for fear of a few. The guilty may slip through; but the innocent will certainly suffer.

But in the meantime, it signals to voters that their Chief Minister is willing to gamble with legality in pursuit of politics. It weaponises Aadhaar, not as Parliament intended—to deliver services fairly—but as an instrument to shape the electorate.

In India, law must speak louder than fear, and louder still than electoral calculation. Aadhaar is a legal right, not a political chip. The courts may yet be called upon to remind Assam’s government of that simple truth.

(Sanjay Hegde is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined