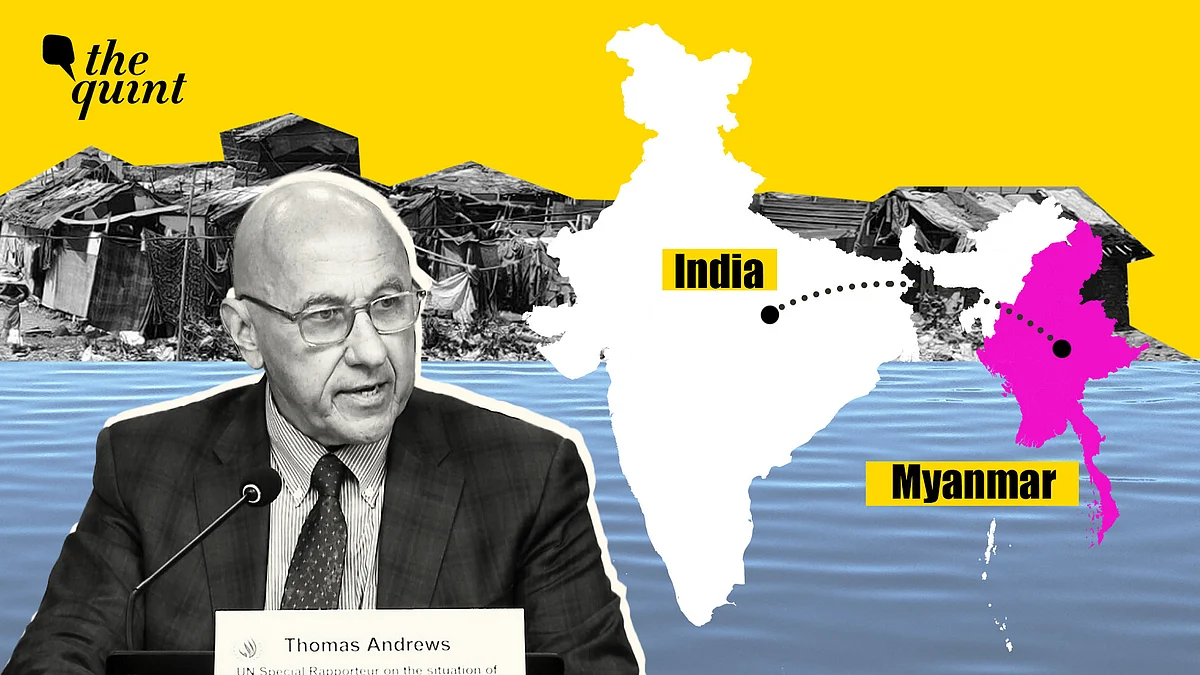

'Dangerous, Can Become a Pattern': UN Expert on 38 Rohingyas Forced Into Sea

In an exclusive interview with The Quint, Thomas Andrews confirmed that a 'probe' into the incident is underway.

advertisement

“We're engaging with the government on this question—and seeking more information and response. There will be a clear demand for those who are responsible for this to be held accountable,” Thomas Andrews, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, told The Quint days after 38 Rohingya refugees were allegedly thrown into international waters by Indian officials.

These Rohingya refugees – including minors, women, the elderly, and the critically ill – all of whom were registered with the UN High Commission for Refugees in India, were detained by the Delhi Police on the night of 6 May under the false pretence of biometric data collection. A few days later, officials reportedly threw them off the coast of Myanmar — the very country they had fled in the first place.

A former US Congressman from Maine, Andrews' mandate currently is to monitor and investigate human rights violations in Myanmar. In an exclusive interview with The Quint, the human rights expert confirmed that an “investigation into credible reports” of the said incident is underway.

“This would constitute a gross violation of international law,” Andrews said, calling the allegations “deeply disturbing.”

'Probing the Incident, Seeking Clarification'

Since the alleged incident, multiple reports of Rohingya deportations have surfaced. Late last week, Indian authorities reportedly removed around 100 Rohingya refugees from a detention center in Assam and transported them to an undisclosed location, eventually pushing them across the border into Bangladesh.

Despite the severity of these claims, there has been no official statement or clarification from the Indian government.

“We have communicated with the Indian government and we are awaiting a response,” Andrews said. While he declined to share the contents of the communication or confirm whether a response has been received, he added,

When asked for a response to the incident, an official from India’s Ministry of External Affairs told The Quint that they have “no comments to offer”.

'This Could Become a Pattern'

Initial media reports paint a grim picture of the events. Since the group reportedly floated their way back to Myanmar on 9 May, concrete updates have been scarce. The lack of official information has raised doubts, with questions emerging about the credibility of the narrative. However, Andrews stood by the reports his office had received.

For the families left behind in India, deportations have been nothing short of traumatic. Relatives interviewed by The Quint describe how their family members vanished overnight, only to hear days later that they had been forced onto boats, abandoned in the sea, and left to fend for themselves. Some haven’t heard from their relatives since.

“The danger is great that this can happen again—not just for these individuals and their families, but for those who could be in the crosshairs of future action. This could become a pattern. It was important to make these concerns public, to make a public statement about this, because of just how egregious this is.”

‘They Deserve to be Heard and Believed’

Despite testimonies from families of those deported, a recorded conversation, media reports, and an ongoing UN investigation, the Supreme Court dismissed a petition claiming that the Indian government’s actions were in breach of domestic policy, international law, and human rights legislation. Their lawyer, Colin Gonsalves, presented the evidence and asked why the government had failed to deny the accusations.

Justices Surya Kant and N Kotiswar Singh dismissed the plea as “fanciful,” describing it as “a beautifully crafted story” with “absolutely no material in support of the vague, evasive, and sweeping statements made.”

Gonsalves informed the bench that the deported individuals had reached out to their families, and that a recorded conversation existed which could be authenticated. Nonetheless, Justice Kant said the petition lacked “prima facie material” and did not offer any solid evidence to substantiate its allegations.

When Andrews was asked about the Supreme Court’s comments, he calmly responded with a smile, "They deserve to be heard and believed because these are credible reports. These are not faceless refugees. They are people—some of whom had built over a decade of life in India—whose sudden disappearance has triggered waves of fear and panic in already vulnerable communities.”

"Aside from any other consideration—the fact of the matter is that people who have escaped conditions in which their lives are at stake, their lives are at extreme risk—there is an international obligation for countries, for governments, to not return them to a place in which they are facing not only detention but perhaps death—that their lives are at risk. This is a fundamental principle of international law, and all countries must respect that principle," he added.

Talking about the method of deportation, he said,

‘Eager to Learn the Process that was Followed’

Notably, India is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol. The fact that India does not have a national refugee protection framework is an argument that has often been used by government authorities, most recently Solicitor General Tushar Mehta in the Supreme Court. The Solicitor General had assured the court that the deportation of “illegal Rohingya migrants” would adhere to due process under current laws.

To that, Andrews said, "I think all countries clearly have an obligation—an international obligation—above and beyond the Refugee Convention. There are clear standards that countries need to follow. And it includes the Convention Against Torture, for example, that the Government of India has ratified."

‘The Eyes of the World are on Them’

What about the "statelessness" of the Rohingya which is purportedly being weaponised? "Let me say on the record that the Rohingyas have been identified by many as the most persecuted minority on the planet. And you see example after example of the persecution that they are facing in the world. You have more than 1.2 million people, most of whom were forced to cross the border into Bangladesh, running for their lives from genocidal attacks from the Myanmar military. They have had to deal with horrible conditions and have been the focus of persecution for years, so they are particularly vulnerable.”

Andrews, in his capacity of Special Rapporteur, a post that focuses on information gathering, said,

When asked whether he believed the actions reportedly undertaken were a violation of International Humanitarian Law, Andrews says, “We’re trying to gather the facts.”

“It's very difficult for me to be more specific about what I hope or expect from the Indian government at this phase. We're trying to gather information, gather facts, understand who played what role in this incident, and get an accounting by the authorities in India as to their view of what happened.”

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined