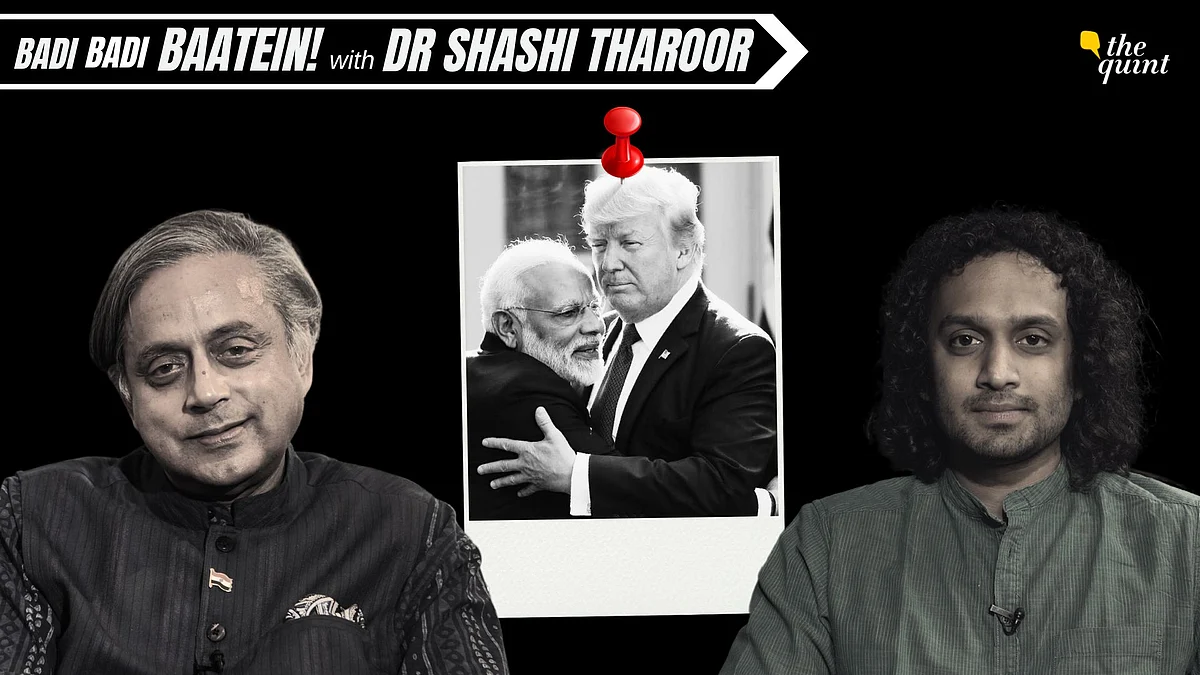

Shashi Tharoor Interview: Did Trump Pressurise India to Stop Operation Sindoor?

On 'Badi Badi Baatein,' Shashi Tharoor talks about his new book 'Our Living Constitution' & India-Pakistan 'war'.

advertisement

Video Editors: Nitin Bisht, Prajjwal Kumar

As peace and normalcy are restored after weeks of military conflict between India and Pakistan during Operation Sindoor, the Narendra Modi government now finds itself in a limbo, with US President Donald Trump taking credit for the ceasefire agreement with Pakistan.

"We will never negotiate with a gun pointed at our head. Why would we give the Pakistanis a negotiation that they could not have won through any other fair or diplomatic means merely because they came and killed 26 of our civilians? No way," said Congress MP Dr Shashi Tharoor said.

Calling 'mediation' an extravagant claim, he also commented on Donald US President Donald Trump's offer to resolve the Kashmir issue.

While Trump's 'interference' in the conflict has irked both BJP supporters and the Opposition, what role did the US exactly play? How legitimate is Trump's claim of 'mediation'? Why is his Kashmir offer an embarrassment for India? In this episode of 'Badi Badi Baatein,' Congress MP Dr. Shashi Tharoor talks about his new book 'Our Living Constitution' and the India-Pakistan conflict.

Why did you feel the need to write a crisp, concise book on the Constitution?

Well, the need to write a book is because of the whole 'hangama' around the 75th anniversary. There were so many debates and speeches, articles, and so on. The publisher said, 'You've got to do a book.' And I said, 'Oh my gosh, I'm working on something else.' He said, Do a quick one. Because what we need is something that's not meant for scholars and lay, you know, academics and lawyers, but for laymen, for regular people who might just read articles in the newspapers about the Constitution but would like to have a broader, more in-depth sense of what it's all about. So that was a challenge.

I'm increasingly discovering, and don't accuse me of writing for the TikTok generation, because I also have hefty books. But I'm also discovering that some of my shorter books have brought attention to subjects they might not have at greater length.

For example, there have been some very good books on Nehru and Ambedkar. And yet, they don't sell that many copies because they're intimidating. There are hundreds of pages and many volumes. Whereas what I have been trying to do with both my Ambedkar book and my Nehru book was to give the relatively casual reader insight into all aspects that matter in these people's lives, what they stood for and what their legacy was.

And to that degree, those two books have done far better than anyone expected. So, using the same logic, you want people to know about the Constitution. Let's not give them something so hefty that they'll feel they've got to be doing an LLB course.

Let it be something that they could have read in a newspaper article, a relatively long newspaper article, 111 pages after all, but which gives them all the 'funda' so that you've got the basic facts and dates and elements and all the key issues, all the debates around the Constitution and sparked off by the Constitution that have occurred are all there. Still, they're there in simple, accessible language without excessive detail or excessive legal citation.

You have written in the book that the principles laid down in the Constitution are the bedrock of Indian society. But what we're seeing in present times is a lot of conflict regarding these principles, be it around language, custom, culture, or religion. Various studies show that minorities are feeling unsafe more and more in this country, which goes against the very basis of the Constitution of India.

Do you worry that the Constitution will become a mere document that is very easy to circumvent because many are saying that not following the constitutional principles is going unchecked and doesn't have consequences, including for people in the political space?

That's not entirely accurate because the judiciary exists to ensure the Constitution is upheld. The fact is that the Constitution is a living document.

It's been amended multiple times, and it can be interpreted differently. Where it is not honoured or violated, punishments are available, and it depends very much on the competent judiciary to impose those punishments for these violations. Quite recently, I read about somebody who defied a High Court order and demolished somebody's unauthorised construction with his bulldozers.

The court made him pay a rather hefty fine, 20 lakhs, to the person whose house he demolished. So the Constitution can be upheld, but it requires a process. Secondly, if you look at the Constitution, Ambedkar Sahib said way back in 1949, he said, 'Look, any constitution, you can write a very good constitution, but if bad people operate it, it'll be a bad constitution. You can write a very bad constitution, but if good people operate it, it'll be a good constitution.' In other words, a lot depends on how we work the blessed document; at different times, it's been worked in different ways.

At the time of the emergency, some cardinal principles were jettisoned. Within 22 months, they were back. There have been many occasions where the Constitution has stood up for itself remarkably well and expanded its meaning. After all, who would have imagined even 20 years ago that you could expand the idea of the right to life to include the right to information and that you could expand that to include the right to privacy?

Suddenly, whole new rights have come into the ambit of the average Indian citizen that were not foreseen when the Constitution was written back in 1947 to 1950. So for these reasons, it's an evolving document. It's a living document, and its relevance will constantly be tested, but hopefully, it will also keep improving.

One basic principle of the Constitution that is mentioned in the book is that India is a land that has embraced many lands. And by that, you meant cultures, customs, languages, religions, and practices. Do you think these basic principles of the Constitution, on the ground level, on the fringes, are a very different reality for people? Is there an actual threat to the constitutional values on the ground level?

No, the values need to be upheld and extended. There are moments in which, sadly, the benefits don't reach people who are unaware of their rights, and those in charge of enforcing them do not uphold the values of the Constitution properly. Let's take some of the tribal areas. There are constantly stories coming out of the tribal belt of violations of constitutional rights. It's not that rights don't exist; people are unaware of this and are not getting a chance to uphold them. So we need to see the extension of these rights and principles to every corner of the country.

It's not that the Constitution doesn't apply or that the Constitution is being willfully ignored. Very often, people are not aware of this, and we need to enhance that awareness. A book like this makes people aware, that's great. If a young person who reads this book is stimulated enough to study more about some rights and then go out and extend them to people in his community who didn't know about them, that's already an accomplishment.

There is usually a lot of debate about the word secular being in the Constitution between the two sides. We see a lot happening in terms of people wanting to be not secular or being identified as secular, and that's the beauty of our democracy. That is right, the Constitution gives them.

But even before and after what we have seen with the terrorist attack that happened, there's a lot of targeting of minorities that happens, particularly of Muslims. For example, when we saw the Pahalgam terror attack, there were attacks against Kashmiris, and there was discrimination against Muslims.

It stemmed from the fact that these terrorists asked about the religion. Do you think the Constitution is not being valued in such instances? Because this has been happening before or after the attack.

No, the values of the Constitution are explicit and beyond debate. This is a secular Constitution, whether you had the word secular there or not. In fact, from 1947 to 1976, the word wasn't there. Because when the question came up, shouldn't we write the word? There was a gentleman who wanted to introduce 'secular' and 'socialist' into the Constitution. I think it was K.T. Shah. At that point, Ambedkar said it's not necessary.

These are policies that depend on the government of the day. Let the government of the day have the freedom to change the policies. But he wrote a Constitution that was, in effect, secular, when you got articles 25, 26, 27, 28 guaranteeing freedom of worship, religion, freedom of assembly, and freedom to propagate your faith.

What's that if not secular? If those are guaranteed as fundamental rights of the Constitution, then whether you have the word secular or not, it is secular. Secondly, the word secular was injected in 1976. And many people in a certain ecosystem objected to it, saying it's a later interpolation during the emergency. However, when many of the interpolations of the 42nd Amendment of the emergency were challenged and removed in the 44th Amendment, that was not removed. And it came all the way up to a court case last year where a judge said, 'Look, de facto it's a secular Constitution, so we can leave it there.'

Whether the word is there or not, it's a secular Constitution. Whether the application of the Constitution is truly secular will vary from case to case and depend on how people behave. You're right that in our country, sadly, particularly in recent years, a certain non-secular approach has gained ground, aRSSnd it's in the texture of ordinary people's lives.

When a Muslim friend comes to me and says, Oh, you know a playmate in his building told my son, my father says I can't play with you because you're a Muslim. It hurts him so much. And my answer is that's deplorable. And you should go out and talk to that father. Ironically, this particular Muslim friend's husband is a Hindu. He should go and speak to that father and say What's the matter with you? He's my son. However, the problem is that this kind of thinking is essentially based on ignorance. It's not based on the Constitution but on social practice. In my mind, we need to increase awareness.

So, during Operation Sindoor, we had two women officers briefing, one of them being a Muslim woman officer, which sent a compelling message to everybody. It sends a message to the Pakistanis. You're trying to divide us into Hindu-Muslim, and we are all united against you, against terror. But it also sends a message to some of the Hindutvadi ecosystem that when you start demonising Muslims, remember you're also demonising this brave woman who's fighting to keep you safe.

You know that is precisely the example that you cited about the child being asked not to play with a Muslim boy. That is exactly what we saw the terrorists wanting to do in this country.

That's right. And that is exactly what, to a certain extent, also played out in this country, where attacks against Kashmiri students, etc., were reported from across. Does it bother you as a staunch follower of the Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb?

Well, what's more, I grew up in India, where it didn't happen. I went to school in Bombay. I had classmates of every conceivable religion and caste, and neither religion nor caste was ever mentioned by my parents when these friends came home to play. I went to high school in Calcutta, and it's the same story. I went to college at St. Stephen's in Delhi, and it's the same story. And that was the kind of India I grew up imbibing, valuing, cherishing. This is the India that the freedom fighters fought for. This is India, and people like Nehruji, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, and others valued and cherished it. This is Gandhiji's 'Ishwar Allah Tera Naam.' It applies to you, too.

The fact is that all of this is something which goes to the heart of who we are and what we are all about. Yes, some people rejected that notion, but I think they are also coming to terms with it. One of the things I have pointed out in this book is that whereas when the constitution was being written, the Hindutvavadi ecosystem rejected the constitution across the board.

They had written the wrong language full of western ideas and British concepts irrelevant to anything to do with India, and on top of that, the most thoughtful critic, namely Mr. Deendayal Upadhyaya, said the problem is that you have written a constitution on the premise that your nation is a territory. You have written a constitution for everybody on that territory. Wrong, he says, 'Your nation is a people, not a territory and the people of India, the Hindu people, you should have written a constitution only for the Hindus.'

That kind of critique is a thoughtful critique, but it's a wrong-minded critique, and it's a critique that is obviously the opposite of the underpinnings of the constitution we have today. Now the descendants of that ecosystem are in power today.

The prime minister says the constitution is his only holy book. The RSS leader Mohan Bhagwat swears by the constitution and says nobody in the RSS challenges the constitution. So we may have seen in the course of the evolution of these last 70-odd years an acceptance of the constitution even amongst those who fundamentally critiqued it.

There was a Congress MP in the constituent assembly, Hanumanthaiyya, who said we wanted the music of the Veena and the Sitar, and you gave us the music of the English band. That was what he said to Ambedkar about this particular draft constitution. But you could argue that it has become much more of the Veena and the Sitar over 106 amendments and over 77 years of practice. Over the whole application of the constitution principles to case after case that were anchored in Indian reality, and now it is indeed the Veena and the Sitar that we are hearing when we talk about the constitution. So I don't think that we should worry anymore about the old RSS Hindutva critique. I believe they have come to accept and come to terms with the constitution as we see it.

Talking about Operation Sindoor, there are a lot of things being said. For different people, that operation played out differently. For the families of the victims of the terror attack, it was about revenge; for people sitting here in Delhi who have no consequences of the war but are calling for it, it was about chest thumping and one up in Pakistan; for the armed forces and the government it was sending a strong message to Pakistan that terrorism will not be tolerated anymore. Lots of perspectives are happening. What are the actual objectives of the operation? Do you think that India has managed to achieve?

I think the most important message we have sent is that the terrorists can't march with impunity, kill our people and march out. There will be a price to be paid, and the nature of that price will keep going up.

In 2015, Uri, you stopped observing the red line about crossing the LOC, you crossed the LoC, and you hit them in the bases that sent the people who had attacked Uri. In 2019, Pulwama, you not only violated the LoC, you violated the international border, and you hit Balakot. In 2025, Pahalgaon, you violated the international border, you violated the LOC, and you went and hit them in the heartland of the Punjab, where 67% of the population lives. But that's where the headquarters of these terrorist organisations were known to be, and we struck them with great precision, striking precisely individual buildings where the LET was known to be training.

Now this is the stuff that sends a very unambiguous message, and I believe that message has been heard. At the same time, we said from the very beginning this is not the opening salvo of a long war, we're not here to fight a long war, we're here to teach you a lesson, and we're willing to stop.

Now, if you fight back, we'll hit hard, you hit us, we'll hit you, you stop, we'll stop, and that's exactly how it played out. It took them three days; they killed sadly 22 innocent people in Poonch, they've hospitalised 59 others, some of whom are still fighting for their lives, so it's not been a good development whatsoever. We've also hit them back, and Mr. Modi said today that 100 people have been killed.

There have been killings on both sides. When they said let's stop, I think India was very willing to stop because we never wanted a long, drawn-out war. We want growth, development, and progress of our people. We are not interested, honestly, in prolonged conflict.

Whatever US President Donald Trump has said, it has done two things. One is that, according to some people, it has made it look like a power as strong as India needed the US's intervention to stop a conflict with Pakistan. Secondly, it has also rallied the right wing against the current dispensation, saying Why did you let them interfere? What can you tell us about the extent of the US's involvement? Because everything, including any official clarification, is sorcery, as they are calling it.

Look, the truth is that there is an awful lot of what's called the fog of war during which many things are being said, many of which can't be verified by ordinary folks like you and me. Some of the basic claims about aircraft being shot down, the number of victims and the number of areas of damage are being contested. Somebody is putting a picture of the Rawalpindi Cricket Stadium, saying it was completely destroyed, while another person picks up another picture of it, saying that's not true. The Cricket Stadium is fine. How do I know without going to the Cricket Stadium? Frankly, I am taking everything with a very generous dollop of salt now.

I don't know what's true. I don't know what's not true. What I will take as an Indian is the authoritative statements of my government when they say yes, we have lost an aircraft, then I will believe it. I don't want to believe it coming from outside sources yet. I do believe that at some point, there will have to be an accounting to the Indian people. But the objectives go beyond calculations of profit and loss.

The objectives have to be about sending a message, and that message, I do believe, has been sent.

How much do you believe the US played a role in brokering the ceasefire agreement?

As far as we are concerned, almost none, because I don't think we needed them to play a role. We had already conveyed from the very start that we don't want to continue (the conflict). We have done our thing. Now you stop, we will stop. If you don't stop, we will hit you back. So, possibly the pressure came from the US to Pakistan, saying you better stop. That's possible.

Mediation is a very extravagant claim. Mediation means that I come and talk to both of you in parallel and relay messages back and forth. From what I know of Indian foreign policy, there is no way that our foreign minister is going to call his American counterpart and say Will you please convey this to the Pakistanis. No way. That's not it. Our foreign minister will say Listen, we have been hit, we are going to hit back. Or if the Pakistanis don't hit us, we have no desire to prolong the war.

That will be a message from us to the Americans. That's it. We are not going to ask them to convey it anywhere else. The Americans, in their wisdom, may call the Pakistanis and say, 'Hey, I was talking to the Indians and this is what the Indians said. So you might be advised to do this—that kind of thing. It's not mediation in a meaningful sense. We always felt that the Pakistani side was the only side with its foot on the escalatory ladder. So if they had been prepared to back off, this war could have ended earlier.

So, in all your experience, because you have even been the Minister of State for External Affairs, there is no way that America could have put a similar pressure on India as they put on Pakistan? No?

Not at all because we weren't the ones who were keen on prolonging the war. Look, there are several things wrong with the statement. First of all, the even-handedness. The equivalence between the victim and the perpetrator. The implication is that there was mediation with India; certainly, there wasn't—the offer of a negotiating forum to the Pakistanis.

We will never negotiate with a gun pointed at our head. Why would we give the Pakistanis a negotiation that they could not have won through any other fair or diplomatic means merely because they came and killed 26 of our civilians? No way. Let them show some willingness. Let them identify and arrest these perpetrators.

Let them dismantle the bases we have struck at Muridke, Bahawalpur, etc. Then we can talk. We are not interested in talking otherwise. And finally, I am not very happy about the re-internationalisation of Kashmir. Kashmir has been off the international agenda for many years now. We should keep it off it. And we are not happy about the re-hyphenation of India and Pakistan. We have de-hyphenated the two.

As recently as this year's Republic Day, when the Indonesian President came to Delhi, he planned to continue to Pakistan. We told him, please don't. We said you wouldn't be welcome if you came and did that. We want you to treat the two as completely unconnected. So, after Republic Day, he went off to Malaysia instead.

That's the kind of de-hyphenation we have insisted upon and we want. I hope we can return to that, and certainly we will not be complicit in any of these things being perpetuated, even by our good friends in Washington.

Donald Trump is coming out and saying that I am offering to help resolve the Kashmir issue. For India, Kashmir has never been an international issue. It has been an internal issue, whereas Pakistan has been trying to internationalise the Kashmir issue. Does it, to an extent, legitimise Pakistan's claim or an attempt to make it an international issue?

If he were to be involved, it would, but that's why we shouldn't encourage him to be involved. We should very gently and firmly convey thanks, but no thanks.

Lastly, you have dedicated this book to Dr. Manmohan Singh. How do you think he would have dealt with an ongoing conflict like this?

Dr. Manmohan Singh remember, is acting in a particular context. When 26-11 happened in 2008, we had seen that happening at the end of a protracted period of peacemaking. There had been the back-channel negotiations with General Musharraf's people. There had been almost near agreement on a settlement. You had the Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi in Delhi that very day, trying to negotiate for a broader, more liberal visa regime.

In that background, you have to see his reaction on 26-11. So he saw it as an aberration. He said we have a civilian government that wants good relations with us. Unfortunately, we have some criminals whom we need to crack down on. And so we tried the route of sanctions, or putting them on the UN Sanctions Committee list or putting Pakistan on the FATF grey list. We did all these things, shared intelligence information, and gave conclusive proof of the Pakistani complicity, much of which was confirmed by British, German, and American intercepts.

All of that was done. And it was hoped that it would teach the Pakistanis a lesson for some time. Sadly, it didn't. Then there was again a peace attempt when Prime Minister Modi became Prime Minister. He invited Nawaz Sharif to his inauguration. They exchanged saris and messages to their mothers. And when he was calling Nawaz Sharif to wish him a happy birthday from Kabul in 2015, Nawaz Sharif said, I'm on your way home. Come and stop by and join my birthday. And he went. And he attended the granddaughter's wedding. And that kind of bonhomie is what preceded Pathankot. So, in the same way as with Manmohan Singh, Modi did the same thing.

He told the Pakistanis that you couldn't really have wanted this done. Please come and join the investigation. Find out who the bad people are who did this. But the Pakistanis sent the intelligence people, and they went back and said, Oh, the Indians did it to themselves. That betrayal was the last straw. After that, Narendra Modi's heart hardened.

And you've seen the tough measures. If Manmohan Singh had been Prime Minister again in 2015, or any Congress Prime Minister, we would have gone through the same learning curve. A government represents a certain continuity, and that learning curve would have played itself out exactly the way that Mr. Modi has played. I fully applaud his crossing the LOC, the IB, hitting the Punjabi heartland, and taking a tough line because we have already tried everything else. We've tried the peaceful alternative. Now we have no choice but to turn a hard heart and a stern face towards Pakistan.

Doesn't Mr Modi's silence on the US's claims speak a lot? It's being questioned a lot. He did not mention the US even in the address, unlike his counterpart, Mr. Shahbaz Sharif.

Yeah, because honestly, we don't give the US any credit as far as I can tell. I don't think the US had any role in our decision to end. We had already signalled from the start that we would end as soon as the Pakistanis did. If they persuaded the Pakistanis, great. But certainly we don't accept the idea that there was any mediation, nor do we accept the idea of mediation.

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined