'Rise Of the Violent Male': Grandson Imagines Gandhi's View of Today's India

Gopalkrishna Gandhi discusses Gandhi's fading influence and India's political future.

advertisement

"Those who speak against it (communal violence), their decibel levels are much lower than those who let it grow. That is what is of concern. And it's not Hindu male, Muslim male, it is just the violent male. Fortunately, that violent male is not so numerous but he is very active," said Gopalkrishna Gandhi, former diplomat and grandson of Mahatma Gandhi.

Many ask: has Gandhi's ideology been forgotten in today's political picture? However, that is not the only pressing question being asked. Today, we also live among those who openly worship Gandhi's assassin Nathuram Godse. What do the descendants of the Mahatma think of it?

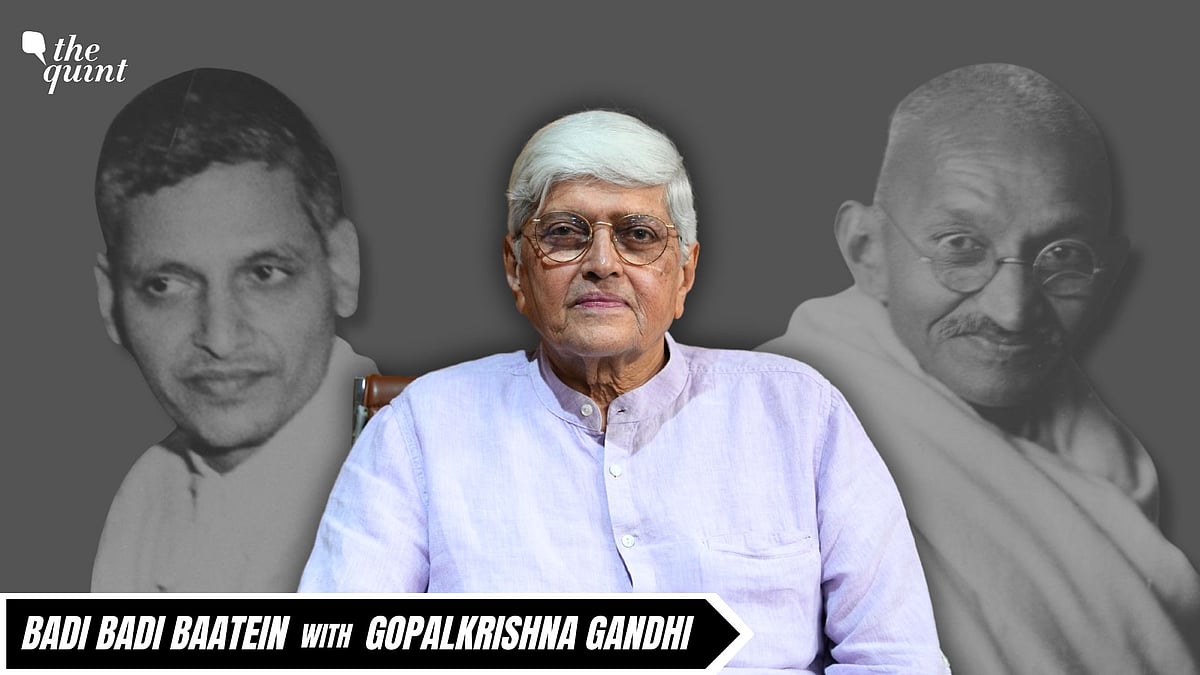

In this episode of 'Badi Badi Baatein', Gopalkrishna Gandhi speaks about the fading memory of Mahatma Gandhi in modern India, the communal discourse of present day Indian politics, the faults in the Congress Party, and Narendra Modi and BJP's claims to Mahatma's legacy.

Sir, welcome to The Quint and welcome to my show ‘Badi Badi Baatein.’ I would like to begin by showing you this picture where you are a very little boy. The significance of it comes from when and where it was taken. Can you tell the story behind this picture?

I can only tell it from what I have heard because I have no memory of it myself. I was just two and a half years old. There is a rite of passage called Sanchayan where the ashes of the cremated are collected by the family, a day after or so of the cremation.

I think the first of February 1948, after the cremation of Mahatma Gandhi was over, the family went to collect the ashes in the Sanchayan. So, I was just loitering around, playing with the sand on the riverbed of the Yamuna. And this photographer just captured that moment. I don't know what he found of interest in it, and I have been captured doing something which I have always been doing, which is playing around with the sands of time meaninglessly.

There was something very interesting that I found right at the beginning of the book, where you say that the name of Nathuram Godse, the man who assassinated Mahatma Gandhi, it wasn't taken very frequently in the family growing up, nobody spoke much of him. Why so?

I think it has something to do with the influence of the man who had been assassinated, his influence in the family, not to be vengeful, not to be vindictive, not to think of somebody as wholly mistaken or evil. The fact of the assassination was very prominent in the family's mind, but not the assassin, and I am rather grateful for that. There was no bitterness in the family. There was revulsion at the act, but no bitterness about the man to the extent that two uncles of mine were very keen that the death penalty should not be handed to the assassin.

Prime Minister Nehru at that time was not fully in favour of the death penalty for Nathuram Godse. Did the family have this dilemma as well?

Gandhi himself was completely opposed to the death penalty. Nehru was opposed to the death penalty for most of his public life. Before he became Prime Minister, that was his position, and that was how we felt about it. My father was the editor of the newspaper; I don't believe he was against the death penalty. In any case, he did not editorialize on the subject. But the death penalty was just one aspect of it. The assassination itself was a matter of immense sorrow. It was not a subject of political contention. We did not view the world in terms of those who were agitated by the assassination and those who sort of defended it. That was not how it was; it was a tragedy.

So, when in today's day and age when we see certain people celebrate the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi around 24 pointing pistols at posters of Mahatma Gandhi in today's day and age when such things happen, do they personally bother you?

Thankfully no. I don't at all. It has never surprised me that some people are not just defensive of the assassination but look upon it very differently. I have always been aware of that. I must also say that we were aware of the fact that around the time of the assassination, there was some violence which had been meted out to certain communities associated with the assassination, and all of us were pretty revolted by that because we knew that Gandhi would have been revolted by it.

There is a very interesting statement by your brother Rajmohanji's wife that you have mentioned in the book, and I quote that Mahatma Gandhi has lost all relevance for India's urban electorate. Do you agree with this statement?

See, there is something called the moment, which is very transitory, and then there is something called the longer influence, and the one person who would have no issues about not dominating the moment is Gandhi himself. He would like India to address its agonies and embrace its triumphs without referencing him. He would say, I am imagining, and I am probably presuming that I have done my bit, now let me be. You handle the moment; handle the relevance of the times by your own Viveka and Buddhi.

You have spoken at length about the Ram Mandir movement and the politics that you have seen over the years on the Ram Mandir movement. If Mahatma Gandhi were alive today, how do you think he would perceive a movement like the Ram Mandir movement?

Well, first of all, he would be 150 plus if he were alive today. That apart, I think, he would see any movement, not just the one that you mentioned. He would just see any movement by its intention, but more by the means adopted. For him, means were much more important than ends, and he could call off something if he felt the means were slipping out of his hands. He would say, mind the means, the ends will look after themselves.

Do you think he would have disagreed with the means by which the Ram Mandir movement was conducted over the years? Say the demolition of the masjid, the opening of the locks, etc., the violence, the riots that took place later.

I would say it doesn't matter whether he would have disapproved. What is important is how we look upon the violence of such a position? How do we look upon the prospect of violence today? Something which is likely to inflame emotions and feelings and lead to violence. How do we perceive it? Gandhi would have said what he would have said. But I think it's far more important that we ask ourselves what we are doing, are we thinking about helping to heal wounds or causing wounds to go deeper. But I am aware of this essential truth that in our society today, hatred, suspicion and violence have a certain play which is dangerous.

Do you think it's politically propagated this mindset?

I would say the possibility of it spiraling is very high, and those who speak against it, their decibel levels are much lower than those who let it grow. That is what is of concern. And it's not Hindu male, Muslim male, it is just the violent male. Fortunately, that violent male is not so numerous but he is very active, we must know this against women, against Dalits.

Do you think the politics which heavily relies on the idea of Hindutva there are times when that politics gets redefined as politics of hate against minorities, specifically Muslims. Do you think with time India misses a figure like Gandhi who stood for a far more inclusive idea of Hinduism?

He believed in humanism. I don't think he wanted to humanize Hinduism or make Hinduism inclusive. He wanted India and Indians to be more human. He knew the extraordinary defects of every community, including his own, which was Hindu. He was a very devoted and pious Hindu, but he saw Hinduism as a human being. He had very strong things to say against Christian and Islamic social customs, also. So, he was not just against what may be called Hindutva. I think he was against what should be called ‘Ahimsa Virodhi Hinsak Bhavnayein’ in all communities.

You have seen the Congress party very closely over the years How do you perceive the present-day Congress? Because there is a general sense that it is failing as an opposition party in this country to be able to counter the ideology of the BJP. How do you perceive the Congress as it is today?

I see your point. I don't think Congress is in its best health today. But is what is happening to the Congress something to do with the Congress, or is it something to do with us as a society? That is, I think the more important question. It is not Congress's problem alone. There are people there with tremendous guts with tremendous integrity. It is very difficult now to find a person in any party with all these- integrity, intelligence, courage, lack of ego, and love of India. It is very fine to say the Congress is not setting a great example. True. But who is? So, where does that lead us? Does it mean that it is all over? Certainly not. Certainly not.

That is where I would like to take your question forward one step. The fact that you are asking this question is our biggest hope because most young people ask this question. My fear is that young people should not give up on politics and political parties as such, because their example is depressing. They should not. I look forward to a time not in my lifetime but perhaps a little later when a new generation will not say no to politics but yes to a new politics, and take India forward as exactly what happened 120-130 years ago.

How do you consume your news today? Do you consume it via newspapers? Do you consume it on your phone? Or do you watch TV news?

It is multi-mode. What is very difficult now to find is silence. You have so many options. When you end the day when you are charging your machines, how many machines you are charging with so many wires you don't have enough plugs. You don't have three-point plugs, two-point plugs.

Despite so many mediums for consumption of news, there is this constant accusation that the media has become more stifled than before. Do you think it is fair to draw these parallels of how the media functioned during the emergency and how the media is functioning today?

There is one word which applies not just to media, but to politics and public life in India, and that is manipulation. Manipulation is now a hydra-headed monster. It can be done in many ways. It can be done through money. It can be done through intimidation. It can be done through just cunning.

Media can get manipulated in many, many ways. But I must also say that today's Indian media scene has many examples of complete independence. People speak their minds very freely, perhaps not without fear, but freely with some element of fear they may overcome. But I do see, in all kinds of media, particularly social media, clear signs of that flame of press freedom remaining very strong.

In British days, when they banned newspaper printing, they came in Cyclostyle version; and Mahadev Desai said on the mast, ‘I change but I do not die.’ So, the media will change; media's freedom may change. It will not die.

You have taken a lot of cinematic liberties through your book. You have mentioned your love for ‘Mughal-e-Azam’, ‘Do Bigha Zamin’ have really impacted you when you watched them. And then you went on to say how films like these in that era really shaped the way people thought, really shaped the way people took interpersonal relationships, inter-religious relationships, etc. But in the recent past we have seen several movies like ‘The Kerala Story’, ‘The Kashmir Files’, very recently ‘Chhaava’ leading to a lot of dog whistling against one particular community. To what extent do you think this argument is fair that cinema really influences the way people think and really reshapes the ideologies of masses?

The power of the moving image is not to be questioned. There is no doubt that it is the monarch of opinion-making, and especially among the young. Among the young, it is an absolute monarch. There is no getting away from it.

So, a huge responsibility lies on those who make films and distribute them. And this is where I would say the depiction of violence, even when shown as something evil, is very dangerous. Depicting anything from contemporary life or from historical lore can inflame passions. And so, a censor board has a huge responsibility in this. It must show its ability to see the possibility of social and communal violence through an indirect depiction. Something which is subtle which shows something which doesn't immediately look like dangerous but is likely to be dangerous has to be taken into account. Playing with the minds of people is a huge responsibility.

You mentioned how in 2014, when Mr. Modi became the Prime Minister, you wrote him an open letter via one of the newspapers and you said he might keep Savarkar in his heart all he wants, but his mind must that be of Ambedkar. But you forgot to tell him that his soul must be that of Gandhi. He has invoked Gandhi many times in his speeches, in his political narratives in the party's line of ideology etc. Do you think that there is a particular party today or for example the BJP, do you think they represent what Gandhi stood for?

Do you think that question should be asked of me or of them?

Do you think there is any party today that has truly taken forward Mahatma Gandhi's legacy?

I do not think there is, but I do not bemoan that there is not for the reason, as I said earlier, that the future of India is much more important than the future of Gandhi in India; and Gandhi would be the first person to say so. He has done what he has, and I think it is up to us now to not lean on him or ask what he would have done, but ask ourselves what we should do.

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined