Branded Illegal: How Over 8,500 Families Were Uprooted in Ahmedabad's Demolition

"My daughter keeps asking when we’re going home, but there is no home left," said Rukhsar, a domestic worker.

advertisement

Salma, a mother of two, stood beside what was once her home in Ahmedabad’s Chandola Lake area, holding a plastic bag of medicines her children depend on.

“We have no clean place to sleep — forget clean water,” she said. Her children have developed diarrhea, fever, and have stopped attending school. In this heat, I used to bathe two or three times a day, but I haven’t been able to bathe for seven days now."

A resident holds a photo of happier times in Chandola, a stark contrast to the current devastation.

Photo courtesy: Marhaba Hilali

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack, nearly 1,000 residents of Chandola were rounded up the very next day, labeled as “illegal Bangladeshis,” and forced to walk 6 kilometers to Lal Darwaza police station under the scorching April sun.

With temperatures soaring, they were made to march like criminals, hands raised, some without even a chance to wear slippers.

They were held in custody for seven days, and despite presenting valid documents, only 200 were identified as Bangladeshi nationals and detained.

The demolition process in Chandola was marked by inconsistency and a lack of transparency. While some residents reported receiving prior notices about the demolition, many others stated they were given no warning at all, leaving them unprepared for the sudden loss of their homes.

The majority were Muslim migrant workers from Indian states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Rajasthan. Despite holding valid Indian citizenship documents, many were branded "illegal Bangladeshi immigrants" and displaced en-masse.

Salim Shaikh’s makeshift tent, a temporary shelter for his family after their home was demolished.

Photo courtesy: Marhaba Hilali

The Anatomy of a Demolition Drive

On 26 April, police personnel entered the Bengali Vas locality near Chandola Lake. According to a report by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), 890 people — 457 men, 219 women, and 214 children —were detained.

The report said they were taken to the Kankaria Football Ground and made to sit outside for several hours. Family members said they were not informed of their whereabouts.

PUCL stated that identity documents such as Aadhaar and voter ID cards were dismissed as forged in several cases. The group reported that many of those detained were Indian citizens from Bihar, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and West Bengal.

According to the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), over 10,000 "illegal structures" were cleared in the Chandola Lake region between April and May. However, testimonies from those affected reveal that entire neighbourhoods were targeted without prior consultation, legal notice, or viable resettlement options.

Salma displays valid documents, proving her rightful residency amid accusations of being an “illegal Bangladeshi.”

Photo courtesy: Marhaba Hilali

The operation followed a terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Kashmir, after which nearly 1,500 men from these settlements were detained in a crackdown. While only 200 individuals were eventually identified as undocumented immigrants and deported, the label of “illegal Bangladeshi” was used to justify the removal of thousands.

On 29 April, as bulldozers moved in, 23 residents of Siasat Nagar filed a petition in the Gujarat High Court seeking an immediate stay on the demolitions.

The petition argued that authorities had not issued prior eviction notices or provided any rehabilitation plans, in violation of a Supreme Court directive mandating proper notice even in cases of encroachment.

The petitioners also cited state slum resettlement policies (2010 and 2013), under which long-term residents should qualify for housing.

The High Court, however, declined to stay the demolitions. In its oral order, the court stated that intervening would amount to "perpetuating illegal occupation" and concluded that settlers had no vested right to remain, given that the land was government-owned and designated as a water body.

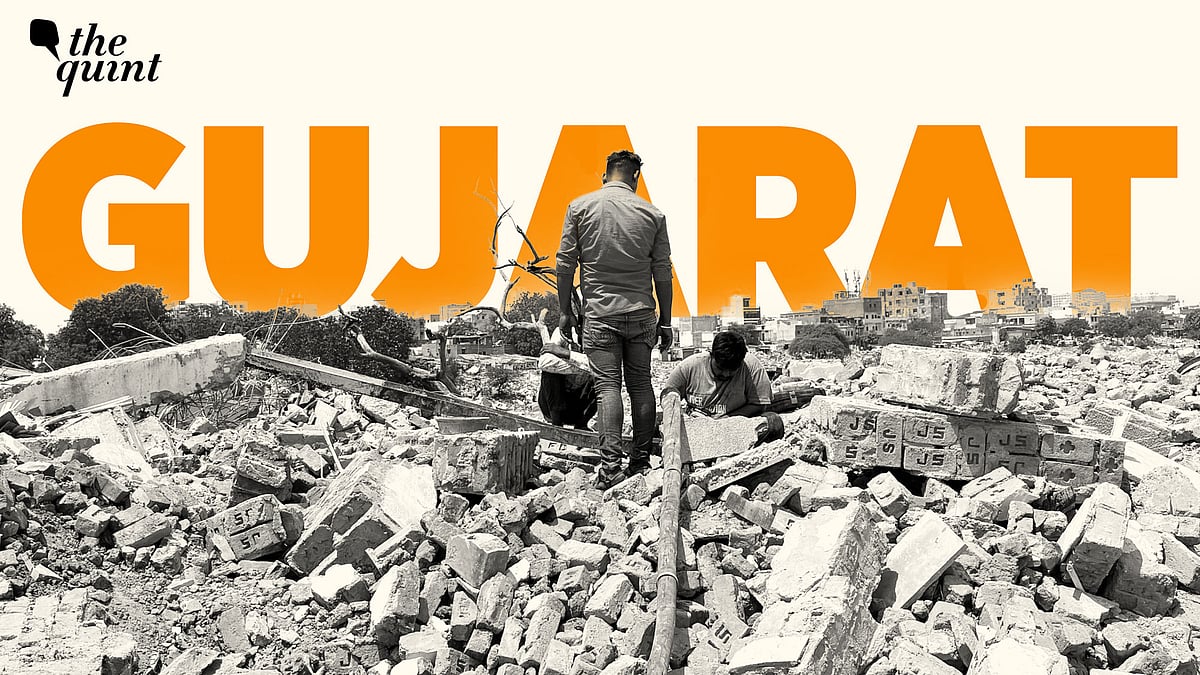

Residents salvage iron and steel from the ruins, desperate to earn money for survival.

Photo courtesy: Marhaba Hilali

Legal Experts Call It Illegal

Pracha adds that such demolitions are often not about legality at all. “These actions are typically done with oblique motives — either political or commercial. It’s about clearing land for vested interests. And because the poor can’t fight long legal battles, the state gets away with it.”

The irony, he pointed out, is that the very same authorities who initially allowed these settlements, often accepting bribes, are now destroying them without facing any consequences.

From Homes to Tarps: Living the Fallout

This is not the first time Chandola has faced such a calamity, In 2018, a devastating fire gutted 500 homes in the colony. while no human lives were lost, many animals perished, and residents suffered immense losses.

Back then, people scarped together funds from various sources to rebuild their homes. Now, seven years later, the government has demolished thoses very homes again.

Salim Shaikh’s children play amidst the ruins, finding moments of resilience in a shattered community.

(Photo Credit: Marhaba Hilali)

Many of these communities had built their lives around the area, working as rag-pickers, scrap dealers, daily-wage labourers, domestic workers, and more. Some families had lived there for as long as 30 to 60 years, with homes passed down across generations.

Several families are now living under plastic tarps, rented verandas or roadside shelters.

In places like the Bombay Hotel, where many evictees moved post-demolition, rents have soared, and landlords demand steep deposits from desperate tenants. Toilets are scarce. Open defecation is on the rise. Diarrhoea, rashes, and viral infections are spreading.

Medical reports of Salma’s daughter, Shab e Noor, highlighting the health challenges faced post-demolition.

(Photo Credit: Marhaba Hilali)

Surveillance, Selective Targeting and The 'Illegal Immigrant' Tag

In a press statement, the Gujarat government claimed the drive was a necessary step to “remove infiltrators and restore order.” But no public list of verified foreign nationals was released. Moreover, the targeted areas were not random — they were predominantly inhabited by working-class Muslims.

“What we are witnessing is surveillance-backed displacement,” said Siddiqui. “First, you monitor communities under the pretext of national security. Then, you use that data to label them suspicious. Once the label sticks, demolition becomes acceptable.”

Bulldozers clear land near Chandola Lake as part of the municipal demolition drive. Once home to thousands of families, the area now lies barren under heavy machinery.

Photo courtesy: Marhaba Hilali

He further added, "I saved 2 Lakh rupees for my father’s cancer treatment, I had to give that money as a security deposit to the landlord. We were happy in Chandola, though there was hygiene and sanitation issue in the locality, but I owned a two-storied home. The women of my house had privacy and a room to rest after tiring day of toiling in textile factory. But we are homeless now. Now our only shelter is this sky. At least no one can take this sky away from us."

Housing Schemes and the Mirage of Legal Shelter

The evictions at Chandola Lake have highlighted structural issues with urban housing schemes. While families are theoretically eligible for rehabilitation under government programs, implementation has been inconsistent.

Many evicted families had applied multiple times for benefits under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) but were either rejected or remained waitlisted for years.

According to AMC Standing Committee chairperson Devang Dani, displaced families would be considered under a joint PMAY-Gujarat housing program— but only if they could prove residency in the Chandola area before 1 December 2010.

This cutoff originates from Gujarat’s Slum Rehabilitation Policy (2010), which requires two forms of documentation, such as older ration cards or voter lists, to verify long-term stay.

A family seeks refuge under a tree, their only shelter in the absence of their destroyed homes.

(Photo Credit: Marhaba Hilali)

AMC reported that around 3,600 housing forms were distributed to evictees at local ward offices after Phase 1. However, thousands more were unable to apply — either because they lacked documents or did not meet the eligibility criteria. For those who qualify, the process remains delayed and is not cost-free.

Local Support Amid Political Neglect

In interviews with residents, a recurring theme was the stark contrast between local support and the absence of higher-level political engagement.

Municipal Corporator and opposition leader, Shehzad Pathan, who residents credit for some relief distribution, are rare exceptions. “He helped with food and clothes,” Salma said. “But how long can one man carry the burden of 8,000 families?”

A System Built to Exclude

The demolition drive in Ahmedabad is not an isolated incident. Across India, informal settlements are razed in the name of development, law and order, or national security — often without due process and almost always without rehabilitation.

Advocate Huzaifa Ujjaini, who serves as the secretary of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), shared their concerns regarding the Chandola demolition drive.

"An atmosphere was created in the name of 'national interest' where any civil rights group protesting the demolition was labeled as 'anti-national.'"

The media sensationalized the issue, fostering a narrative against the Chandola colony to ensure the demolition was not perceived as anti-human.

The activist, who has closely followed demolition drives across Gujarat, observed a similar pattern in Dwarka.

There, too, a narrative was built claiming that the proximity to the sea posed a security threat due to potential movement of Pakistanis, thereby justifying the demolition.

Without prior notice, around 500 homes of Muslim fishermen in Bet Dwarka were razed, rendering them homeless. The media similarly attempted to desensitize this issue, downplaying its human cost.

What ties them together is a recurring pattern: legal violations by the state, the misuse of administrative machinery to aid land acquisition, and the near-total absence of accountability.

Back in the Bombay Hotel area, where hundreds now sleep under tarpaulin sheets or in rented sheds, families are struggling to get their children back into school. Clinics nearby report rising cases of skin infections, respiratory illness, and diarrhea among evictees.

Chandola, once a lively community, is now a pile of rubble under Ahmedabad’s blazing 45-degree heat. Broken homes are surrounded by dust and debris, making the area feel empty and hopeless. Residents, with despair on their faces, struggle to find water from outside sources since basic facilities are gone.

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined