'My Chennai Society Was a Biohazard—Now We Recycle 75,000 Litres Daily'

We’re just residents who got tired of flushing our problems away—and decided to do something about it.

advertisement

Every Sunday morning, our 66-year-old neighbour, Venkat uncle, takes his torch and newspaper and heads downstairs—not for a walk, but to check on our sewage treatment plant.

Yes, we have a sewage treatment plant in our apartment complex. No, it wasn’t built by the government.

And no, we’re not some luxury green housing society.

We’re just a regular bunch of residents who got tired of living with the stink, and the bills, and the feeling that no one was ever going to fix it for us.

So, we fixed it ourselves.

'Not Just the Smell, But the Helplessness'

We live in Central Park South, a 172-flat complex in Sholinganallur, Chennai. Like most buildings on Old Mahabalipuram Road (OMR), we depended entirely on tanker water. Each flat paid Rs 3,000-4,000 a month, sometimes more.

Meanwhile, our underground sewage system was collapsing.

And somewhere in all that frustration, someone asked: Why are we paying to live in our own filth?

'From That Question, To The Movement'

We didn’t get angry. We got curious.

A few of us started looking into sewage treatment systems. We weren’t engineers. Most of us didn’t even know what "effluent" meant. But the more we read, the more we realised we could do something small, simple, and entirely on our own.

In 2023, we pooled in Rs 8 Lakh. We found a consultant. Hired a contractor. When he left halfway, we rolled up our sleeves and finished the job ourselves

We literally waded through sludge. We argued over pipe fittings. We learned on the go. And somehow, it worked.

'I’m Not Flushing Pee Water,' Someone Said

Oh, the early days.

People were worried it would smell. That it would ruin their property value. One person genuinely asked if they were now going to flush “pee water.”

Instead of brushing them off, we educated. We hosted basement meetings. We called them "toilet talks". We explained the process, shared photos, even brought in experts.

Slowly, the fear turned into fascination.

Now? The same neighbours say, “Our water is recycled. Is yours?”

'What We Actually Built'

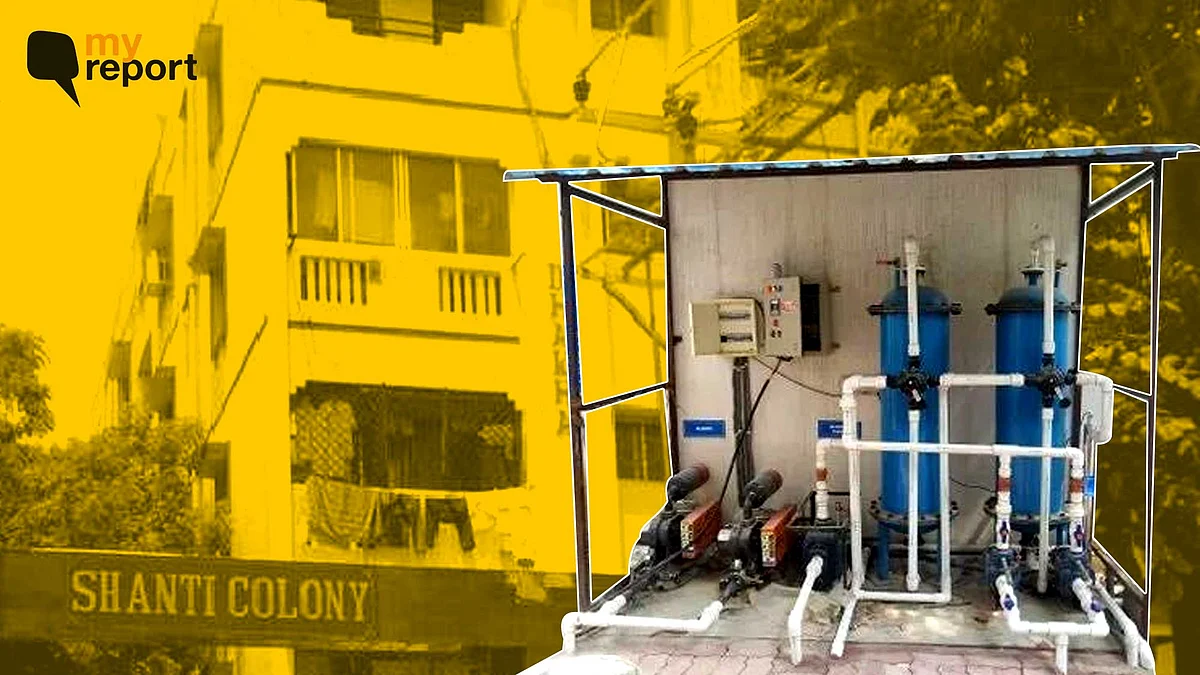

We built a decentralised sewage treatment plant that treats 75,000 litres of wastewater a day.

It uses a method where bacteria naturally break down the waste in moving biofilm reactors. After treatment, the clean, odourless water is stored and reused for flushing and gardening.

We also built 43 rainwater recharge pits across the campus. During the monsoon, we don’t use a single drop of tanker water. Even our borewells are healthier now.

The best part? It’s maintained by us. Our plumber, Arjun, now checks pH and BOD levels daily. He didn’t know what those meant four years ago. Now, he trains others.

'The Impact Is Real—and Ongoing'

We've cut our water bills by half. We’ve reduced our environmental impact. But more than that, we’ve created a culture of accountability.

Every month, residents take turns overseeing the system. Our WhatsApp group is filled with photos—not of food or forwards, but of clean tanks, flow readings, and garden updates.

Teenagers ask how water testing works. Grandparents share advice on waste segregation. Something changed—not just in our pipes, but in our minds.

'Just Down the Road, the Story Is Different'

Sangeetha, a single mother of two, lives in a building 500 metres away. She spends Rs 2,000 every month on tanker water, and another Rs 1,200 to clean her septic tank. Her corridor floods every time it rains.

"That’s just how it is on OMR," she says. But we don’t think that’s how it should be. That’s why we’ve started sharing what we’ve learned. We’re helping other apartments plan their own STPs, calculate costs, and convince their builders.

We don’t want to be the exception. We want to be the beginning of something bigger.

'We’re Not Heroes, We Just Got Fed Up'

We’re not here to brag. We’re not some elite sustainability project.

We’re just residents who got tired of flushing our problems away—and decided to do something about it.

This story isn’t about sewage. It’s about ownership. About plumbers who became teachers. Grandmothers who understand biofilms. Teenagers who test the water samples.

Most of all, it’s about caring. Because clean water isn’t magic. Someone has to deal with the dirty stuff first.

And in our little corner of Chennai, that someone turned out to be us.

(Jayashree Balakrishnan is an accounts manager at a private insurance firm and a volunteer with the RWA.)

(As told to Baishnavi Sharma)

(All 'My Report' branded stories are submitted by citizen journalists to The Quint. Though The Quint inquires into the claims/allegations from all parties before publishing, the report and the views expressed above are the citizen journalist's own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined