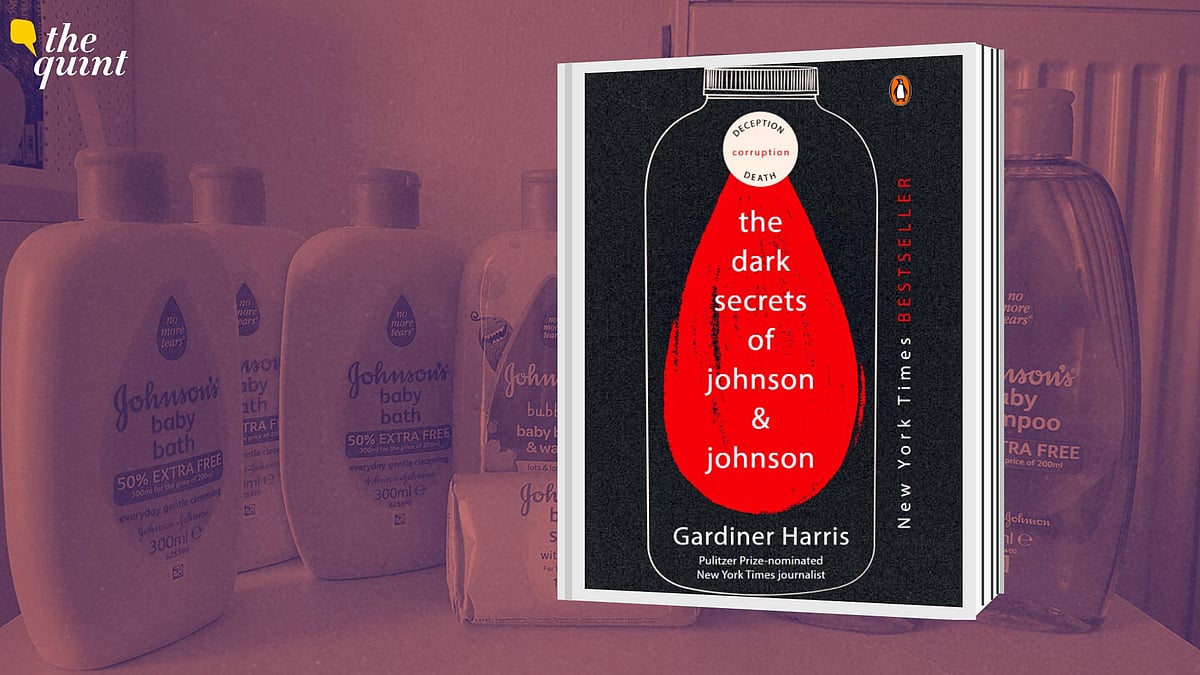

Book Excerpt: The Untold Story of Johnson & Johnson’s Scandalous Track Record

Gardiner Harris uncovers how the trusted brand became a symbol of corporate betrayal and deadly consequences.

advertisement

(Extracted with permission from The Dark Secrets of Johnson and Johnson, by Gardiner Harris, published by Penguin Random House. Paragraph breaks have been added for readers’ convenience).

In 1989, Johnson & Johnson sold its talc subsidiary. Instead of taking the opportunity to transition Johnson’s Baby Powder entirely to cornstarch, as other giants like Pfizer were doing, the company kept buying and using talc. There is no easy answer as to why.

By then, asbestos (and rock dust inhalation of any kind) had become radioactive in American life, and no American mother would sprinkle her baby with anything that had even the remotest chance of containing it.

Still, Baby Powder was just one of several Johnson & Johnson products that used talc.

In 2004, Imerys, Johnson & Johnson’s talc supplier, began placing a cancer warning on every sack of talc delivered to Johnson & Johnson and its other customers after the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that it had placed talc on its list of possible carcinogens.

Concurrently, Imerys executives quietly put together a formal proposal that the industry voluntarily phase out talc-based baby powders, body powders, and dusting powders that women use on their genitals.

Material Safety Data Sheets, or MSDS, are required by law to list ingredients that are potentially hazardous to human health. A few months later, a Johnson & Johnson executive wrote an internal email dated 19 January 2005, announcing that the shipping label for Shower to Shower, a cousin of Johnson’s Baby Powder that was half talc and half cornstarch, would have to include a cancer warning.

Johnson & Johnson had still not abandoned efforts to improve the safety of Baby Powder altogether, having launched a cornstarch version to accompany its original formulation. In 2008, its Global Design Strategy Team tested whether the company should change for good its iconic Baby Powder formulations and packaging to highlight differences between old and new.

They hired Research International, a huge branding and market research company, to survey women, and particularly mothers, about their preferences among four possible versions of Johnson’s Baby Powder, including Johnson’s Classic Powder, Johnson’s Talc Powder, and Johnson’s Baby and Talc Powder.

Sales analyses showed that mothers were already shifting away from talc. The more Todd True, a member of the design team, learned, the more uneasy he became.

In a 18 April 2008 email headlined “Baby Powder—not for babies,” he wrote that,

In response, other team members noted that trying to educate women about the differences between talc and cornstarch might open a can of worms for Johnson & Johnson.

Yes, the company had a safe substitute for talcum powder that to many users is indistinguishable from the original. But could the company suddenly admit that talc was problematic around babies?

True’s proposals were shelved.

Another puzzle is why the FDA didn’t take a stand. Following the 1982 publication of Cramer’s study linking talcum powder with ovarian cancer, a sizable number of subsequent studies confirmed the association.

In 1994, the Cancer Prevention Coalition sent a letter to Ralph Larsen, Johnson & Johnson’s chief executive and chairman, asking the company to stop selling talc. The coalition simultaneously filed a citizen petition with the FDA asking that all talcum powder products contain a cancer warning.

The coalition noted that this was the third such petition received by the FDA. Relying on false reassurances from Johnson & Johnson, the FDA had rejected the first two out of hand.

In response to the third, the FDA co-sponsored a conference titled “Talc: Consumer Uses and Health Perspectives.” The other co-sponsor was the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (ISRTP), which received grants from Johnson & Johnson and CTFA [then Cosmetic, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association], to hold the workshop.

The journal of the ISRTP, Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, was financed in part by the tobacco, pharmaceutical, and chemical industries.

The CTFA sent the ISRTP names of participants the association wanted to attend the talc symposium. Most came from industry, and nine of the 14 academics invited served as talc industry consultants but did not disclose these financial ties.

In the end, the FDA told the Cancer Prevention Coalition in July 1995 that it couldn’t respond to its petition “because of the limited availability of resources and other agency priorities.” This wasn’t just a smokescreen: nothing had changed over the decades in terms of the FDA’s cosmetics office being perennially starved of resources.

But the entire process was too much for Dr Alfred Wehner, a Johnson & Johnson consultant who, in a letter to a top company executive, described multiple statements made in defense of talc to be “outright false” and inaccurate.

(Views expressed in this excerpt are personal.)