Book Excerpt: Being Blacklisted in Pakistan, 26/11 Covert Ops & 'Codename Kesar'

No spy thrillers depicting covert operations in books or movies can match the operations carried out in real life.

advertisement

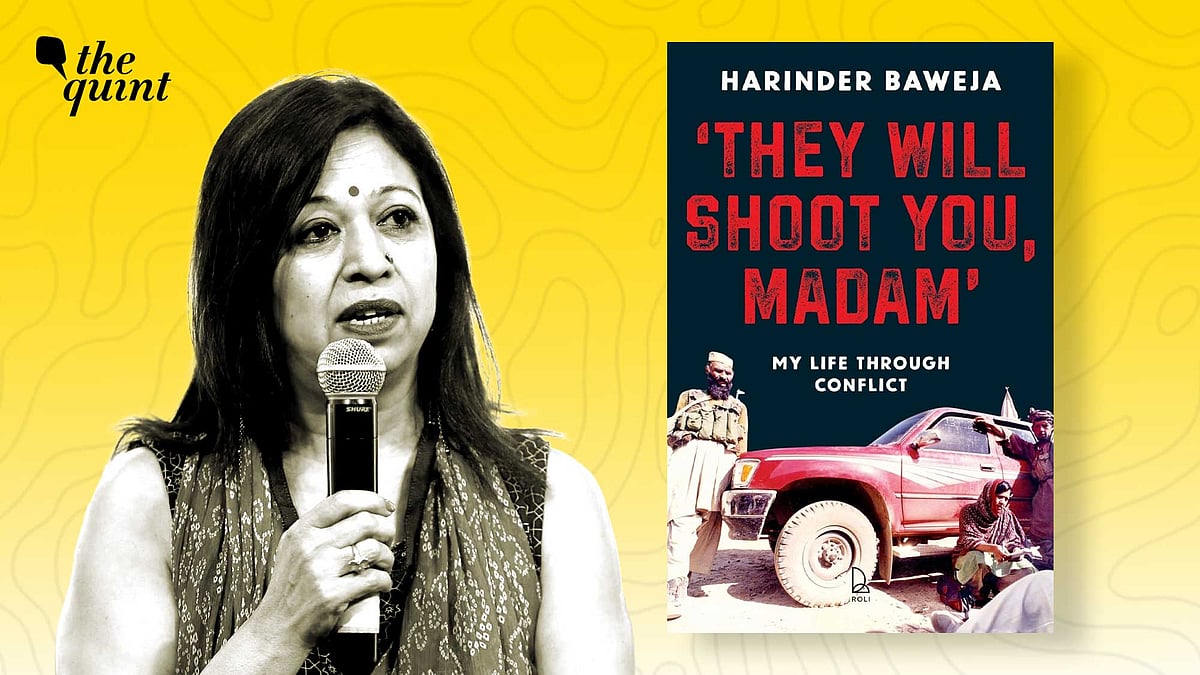

(Excerpted with permission Harinder Baweja's book 'They Will Shoot You, Madam', published by Roli Books.)

A few months after I returned from Muridke in 2008, I learnt that I had been put on Pakistan’s blacklist for a second time.

Covering Pakistan was exhilarating even though Indian journalists are followed bumper-to-bumper from the minute they land and are constantly trailed. The experience is discomfiting. The sleuths in safari suits would perch themselves on a sofa in the hotel – usually facing the elevator – trying to hide their faces behind a newspaper. They’d jump up immediately and kick-start their motorcycles and follow you, every step of the way.

There was no way I could have entered the Lashkar headquarters without the ISI’s clearance. Blacklisting me was just the intelligence agency’s way of saying it did not like what I wrote. The truth is seldom convenient for covert agencies, especially powerful ones like Pakistan’s. They control their own prime ministers and guide the powerful jihadi network, alike.

In India, agencies like the IB and the R&AW deny access to make their displeasure known. In one case, again related to crucial information pertaining to 26/11, an IB officer who had become a good contact just refused to take calls. He was unhappy with an article that had exposed a slip on their part.

A few months before the Mumbai attacks, SM Sahai, a senior officer posted as IG (Crime), in Jammu and Kashmir, had informed the IB of a stellar covert operation in which he and his team had provided Indian SIM cards to the LeT. Sahai had put together a team that managed to infiltrate the ranks of the LeT.

He joined the Jammu and Kashmir police force as a follower – the lowest rank in the police cadre – for a paltry sum of Rs 1,500 a month. But Mukhtar had the appetite for dangerous missions and threw himself – as part of a plan – into a cell in a police station where a hard-core terrorist was lodged. Slowly but surely, Mukhtar built contacts within the LeT, after his cellmate shared a mobile number with him. The number was soon put on a tracking list.

No spy thrillers that encase covert operations – in books or movies – can match the operation that this team carried out. The imprisoned terrorist was desperate to leak the news that he had been caught, so his comrades could flee to safer hideouts. Bit by bit, month by month, Mukhtar gained the confidence of the LeT operatives on both sides of the LoC. His cellmate was an important import and his trust led him to several others. Step by step, he entrenched himself in the ranks of the terror outfit, who, in turn, started believing that he was one of their own.

Then, one day, came the demand for SIM cards for an attack on ‘Watan-e-Hind’. Chillingly, the demand was made by Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, aka ‘Chacha’, also the Lashkar’s military commander. Mukhtar by now apparently had managed to win over the trust of Saeed’s top confidantes.

In the meanwhile, Sahai’s team established contact with a Kashmiri militant, codenamed ‘Kesar’, who had already crossed into Pakistan and was ready to return and be a part of the police force. Kesar was a good – rather, safe choice – mainly because he was a part of the inner circle of the Pakistan-based terror organisation.

This part of the covert operation has never been revealed before. It is definitely not a part of any archival domain. It is unlikely to be a part of official files either, for such sensitive operations are seldom put down in black and white. I sourced it from conversations with several officials of the police and intelligence agencies.

The team arranged for Kesar to cross the LoC into Uri, a district on the Indian side of Kashmir. Since the Indian Army keeps a sharp eye on border infiltration and has orders to shoot to kill, seniors within the organisation were requested to allow the operative to cross over.

Upon his return, a passport was issued in his name, and the next step was to get a visa. This was a relatively easier task than infiltrating the ranks of the terror organisation that was planning a big attack. Why else would they ask for Indian SIM cards?

The visa application was submitted with a written request from hard-line separatist, Syed Ali Shah Geelani, well-known for his calls for Kashmir’s merger with Pakistan, as also for his infamous calendars wherein he exhorted Kashmir’s youth to take to the streets in protest. Geelani’s calendars kicked in at all times: when a militant was killed; when innocents became victims of gun battles between the security forces and the terrorists. Calls for curfew were even issued by Geelani on dates commemorating the anniversary of the United Nation’s resolution on Kashmir.

Sahai’s team was confident that Kesar’s visa would be issued. It was well known within official circles that applications recommended by Geelani were processed within a day by the Pakistan High Commission. Mukhtar was back from Kolkata with the SIM cards and Kesar had a valid visa. The SIM cards were stitched into the pages of a diary and handed over to Kesar, who crossed the land border at Wagah, to return to his comrades, whose trust he already had. Indian officials at Wagah were told to let Kesar pass.

It was time for Sahai to write a note marked ‘Top Secret’ and provide details of the mobile numbers that had been sent across the border to the LeT. It was clear to Sahai that the SIM cards would surface in India but he wasn’t sure about when or where. Sending the note was important because the numbers could not have been monitored out of Jammu and Kashmir. The state police could only request service providers who operated within their domain. In this case, the SIMs had been procured from Kolkata.

Sahai sent the ‘Top Secret’ memo to Arun Chaudhary, the Srinagar-based joint director of the IB with a copy to Kuldeep Khoda, director general, Jammu and Kashmir Police.

It was now the job of the IB to keep a close watch, on where and how the SIM cards were going to be used. One thing was clear: the phone numbers would be put to use in India. That was the only reason the LeT had sourced them. At least three of the over 30 SIM cards, used during the serial attacks in Mumbai, were in the possession of Kasab and his nine compatriots who had alighted at Colaba’s Badhwar Park.

It was only on the night of 26/11, once the terror strikes were well under way that the IB was reminded of the ‘Top Secret’ memo.

Soon, the Anti-Terror Squad (ATS) – who had lost their chief, Hemant Karkare and two other officers, Ashok Kamte and Vijay Salaskar – began recording the conversations between the terrorists and their handlers in Pakistan. The IB was also listening in, in their own control room. By the time the IB officials called the ATS office at about 1 am to tell them, the mayhem in Mumbai had begun.

Several agencies including R&AW had enough intercepts that had warned of a strike in Mumbai but the different agencies sharing information were not joining the dots. This, despite the fact that Taj Mahal Palace Hotel was specifically mentioned as a potential target in the intercepts.

Four days after the deadly attack, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s government quickly changed the home minister, replacing Shivraj Patil with P Chidambaram. In an interview to The Indian Express, in January 2009, Chidambaram rightly said, ‘You will not get an invitation card which says you are cordially invited to come and witness a sea-side incursion into India.’ He was angry and was using sarcasm to drive home the point about the importance of analysing intelligence and being ahead of the enemy.

Journalism, as I’ve practised it, is not meant to suit anyone’s narrative. It must always be an honest attempt at digging facts, chronicling the truth, adding perspective and providing a deeper understanding of how the powerful operate. The powerful can be from within the system or outside of it. The LeT remains a powerful non-state actor.

No one from the LeT has been prosecuted for the Mumbai attacks. Quite to the contrary, Lakhvi or Chacha, the top LeT commander – second only to Hafiz Saeed – who was initially arrested by Pakistan for masterminding the 26/11 attacks, fathered a child while being held on terror charges at the high-security Adiala jail in Rawalpindi.

Abu Jundal, a 26/11 plotter who was with Lakhvi, monitoring the attack on live television, told intelligence officials that Lakhvi’s youngest wife was allowed to visit him in jail, despite him being on trial. While at Hindustan Times, I had reported the news of Lakhvi fathering the child.

Jundal, an Indian had been tracked, arrested and deported to India from Saudi Arabia in April 2012. Jundal told Indian interrogators that Lakhvi shared this information with him when he called on him in Adiala jail to tell him that he had got married.

‘The American government too shared intelligence with India that Lakhvi had access to a mobile phone in jail and that he continued to run the Lashkar’s operations from prison,’ I had written for Hindustan Times in November 2012.

Lakhvi’s current whereabouts are unknown. He was never brought to justice for being one of the masterminds of 26/11. The only solace India can draw is that the UN rejected a petition by Hafiz Saeed asking it to remove him from the list of sanctioned terrorists, twice.

The 2019 report of an ombudsman – endorsed by the UN Sanctions Committee was categorical. Saeed’s ‘argument of dissociation with LeT was not credible,’ the report concluded, adding, ‘He [Saeed] will continue as a listed individual.’

His benefactors in the Pakistan establishment came to his aid by refusing to grant a visa to enable the ombudsman from travelling to Lahore to interview Saeed.

The pious professor remains a terrorist in the eyes of the world. So does the JuD. It is not the charitable organisation it likes to portray itself to be. The United Nations doesn’t think so – it remains proscribed.

Postscript: India could point a firm finger in Pakistan’s direction because it was able to record conversations between the 10 terrorists and their handlers in Pakistan. Mukhtar, who should have been awarded for his gallantry, was instead arrested and jailed for criminal conspiracy and for having links with militants. Intelligence agencies don’t like being outed. In this case, the police had dared and succeeded in penetrating the ranks of the organisation that wreaked havoc in Mumbai. Mukhtar was eventually released and all charges dropped. By then he had spent an agonising three months in jail. No one pins medals on the chests of undercover agents who risk their lives in the national interest.

No medal was pinned but the Modi government gave the defence forces the freedom to strike at the terror infrastructure in Pakistan, after the killings of tourists in Pahalgam.

Out of sheer curiosity, I dialled Waleed, Hafiz Saeed’s son-in-law’s number several times. Each time, a recorded message said, ‘The number you are trying to reach has been powered off.’

Operation Sindoor hit nine targets. For the first time, Indian defence forces targeted the heart of Pakistan’s Punjab which is also the heart of its army domain. The uneasy question that remains unanswered is simply this: Has Operation Sindoor also powered off the terror that Pakistan exports into India?

(Harinder Baweja is a senior journalist and author. She has been reporting on current affairs, with a particular emphasis on conflict, for the last four decades. She can be reached at @shammybaweja on Instagram and X. This is a book excerpt, and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)