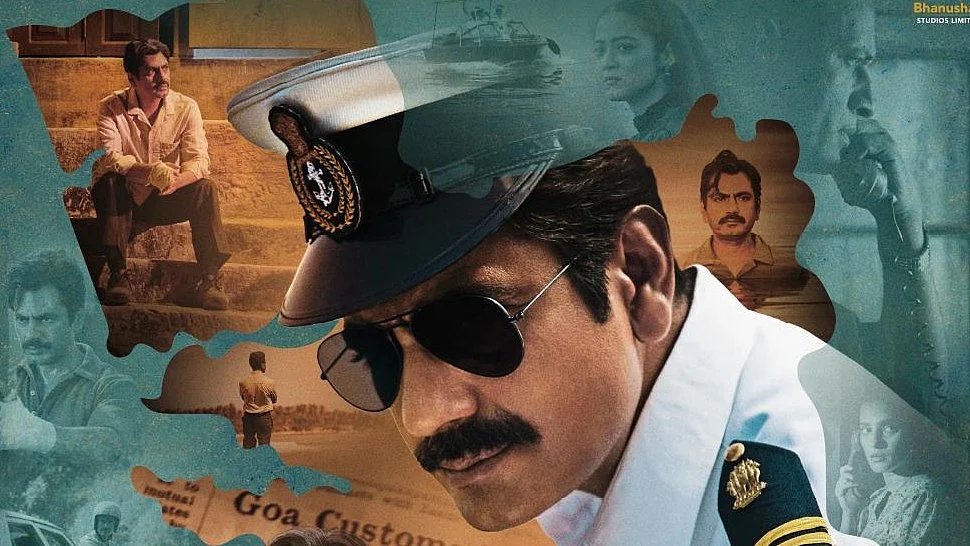

'Costao' Review: Nawazuddin Siddiqui's Lonely, Complex & Periodically Dry Fight

'Costao', starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui as Goa customs officer Costao Fernandes, is streaming on Zee5.

advertisement

At one point in Costao, Costao Fernandes (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), a Goa customs officer accused of the murder of a local politician D’mello (Kishore), says, “That's the problem with our society. Everyone wants a brave officer but not in their own house.” Because courage often comes with a cost, especially for an honest man in a dishonest system.

In the first half itself, the film establishes that Costao did, in fact, kill a man but in self-defense when a mission to bust a gold-smuggling ring results in a fatal altercation. And so begins a fight for survival – the CBI is trying to convict him of the murder and the politician is out for blood. These attempts manifest as humiliating run-ins with officers and sudden attacks, in hospitals and the streets.

There is a template we often see with biopics based on ‘heroes’ like Costao — the protagonist fights an unjust system, winning brawls and solving seemingly unsolvable riddles with sheer will. But Costao is not that kind of hero and neither is it that kind of film.

Costao is less a story of survival and more a story of a man trying to keep himself whole even as everything around him chips away at him and everything he holds dear — Costao even comments that he's ‘rusting’.

Costao isn't an explosive hero – his fight exists with an awareness that he might lose. His enemies are too powerful and as a man abandoned by the same system, this is a lonely fight. In a way, Nawazuddin Siddiqui is the perfect conduit for the role.

There's a well-established Siddiqui trademark – the disgruntled common man living life like he's going through the motions, weighed down by the inevitability of the end of his story. This trademark helps and hurts the film – skewed to the former because the performance is exemplary. But the use of the word ‘conduit’ isn't incidental – Costao exists through Siddiqui. The latter’s recall factor becomes a sheen over the character, making it difficult to distinguish between them when the script eventually lets the character down.

The film, rather absurdly, is narrated by Costao’s daughter. This, along with director Sejal Shah’s decision to spend a lot of the film’s initial runtime to establish Costao’s ‘character’, takes away some of the story’s intensity. Thankfully, the latter is a problem quickly ignored when the film picks up but the former persists, aiding the film in one of its worst narrative choices.

Once the dullness of the first few minutes passes and the action (or the film's definition of it) progresses, it reveals itself to be more than just a ‘one man fights all’ story – it's also a family drama. The accusations leveled against him don't just affect him, they affect his wife Maria (a scene-stealing Priya Bapat) and his kids. Their lives are uprooted and jostled constantly – something that causes an irreparable strain on their marriage.

One of the film's most effective scenes involves an argument between Maria and Costao about his priorities and his frustrations. A silent coexistence follows. Unlike most thrillers, Costao's strength lies in its ability to appreciate the quieter moments – the anticlimactic, non-cathartic moments. The story doesn't proceed as much as it unravels. Ajay Jayanthi’s background score helps the pacing even when the editing is inconsistent.

And that's when the issue arises – the story forgets that Costao was meant to be a layered, flawed character. A character can be selfless and selfish at the same time – a man can be a selfless official and an absent father and husband. While the writing displays ample understanding of the consequences Costao faces, his family ends up becoming a footnote to his story – it's almost ironic that the film ends up making the same mistakes as its protagonist.

Costao works best when it tries to dissect and flip the narrative of what a hero’s fight looks like, especially without a quick fix Bollywood masala solution. And by still trying to force Costao into a ‘he was a good man after all’ ending, the film forgets its own strengths.