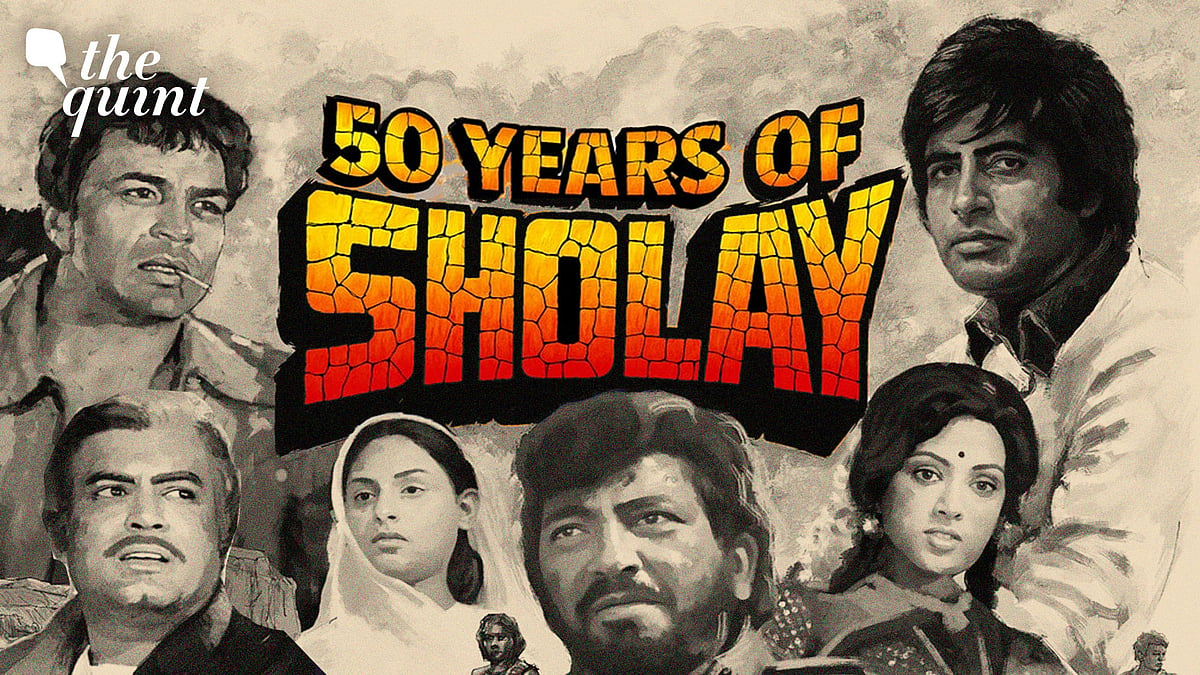

Remembering 'Sholay': Dharmendra’s Pranks, Romances on Set, and That Epic Climax

The most chilling scene in my opinion is the revelation of the fake coin in the climax, writes Bhawana Somaaya.

advertisement

When Sholay was released 50 years ago, on 15 August 1975, I wasn't a journalist. A dear friend from college was friends with the then budding film producer, Boney Kapoor, and he insisted that all of us watch this magnum opus first-day-first-show.

"This film is going to change the history of Indian cinema," Boney emphasised—only that we didn't take him seriously.

The First Time I Watched 'Sholay'

And so, my friends and I arrived at the cinema hall before time. It was a hot afternoon—and there was a large crowd outside. That, in those days, was normal. We were investigating all the film posters when some black marketeers, dressed in jazzy shirts, asked us if we wanted movie tickets. We ignored them and proceeded towards the auditorium.

The single screens in the olden days were divided into three sections—the lower stalls, comprising the front rows usually occupied by staunch film buffs or associates of the black marketeers. This was the crowd that applauded action, whistled during romantic scenes, and threw coins at the superstar’s entry. Then, there were the upper stalls comprising the back rows, often patronised by the middle class. And, finally, the balcony, a smaller space, occupied by the affluent.

Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra in a still from Sholay.

(Photo Courtsey: Sippy Films)

There was laughter at Basanti’s (Hema Malini) endless chatter and wonderment for Soorma Bhopali (Jagdeep) and Jailor (Asarani), but the film was unusually long, violent, and verbose.

A Roaring Success

Sholay proved a phenomenon and ran to full houses at Mumbai’s Minerva theatre for decades. The exhibitors had not witnessed such a roaring success in a long, long time, and the glowing tributes for the movie altered many perceptions.

The following year, in late 1976, I stumbled into film journalism by accident, and worked with top publications of the time. My job entailed me to travel to distant film studios, sometimes production offices and star homes, and everywhere, I unwittingly gathered treasures from the Sholay trove.

Amjad Khan in a still from Sholay.

(Photo Courtsey: Sippy Films)

I remember Amjad Khan telling me that he had no idea that Gabbar was such a special character until all the actors on the sets of Sholay confided to him that they longed to play his character.

Sanjeev Kumar in a still from Sholay.

(Photo Courtsey: Sippy Films)

Jaya Bachchan has fond memories of the film—and said that filming of Sholay in a remote village in Bengaluru, was like living in a lover’s paradise.

Jaya Bachchan in a still from Sholay.

(Photo Courtsey: Sippy Films)

Favourite Moments from Sholay

Over the decades, as I got more entrenched in film journalism, my world view of cinema and writing changed as well.

Boney Kapoor was not off the mark when he predicted Sholay will change the history of Indian cinema. On rewatching the film a number of times, now professionally, I admit that the scale and the taking of Sholay is incomparable, so is the dance, drama, and the emotion.

It takes courage to introduce so many characters and make them memorable. Some films take a while to grow on you—perhaps Sholay is one of them.

Hema Malini and Dharmendra in a still from Sholay.

(Photo Courtsey: Sippy Films)

Another favourite is Veeru (Dharmendra) snuggling Basanti while tutoring her to shoot, and Basanti's candid conversation with the deity. Both so endearing.

I was charmed by Jai carrying Veeru's marriage proposal to Basanti's mausi, but the most chilling scene in my opinion is the revelation of the fake coin in the climax.

A few more decades passed by. I was now an author. In an interview with Hema Malini for her authorised biography, the actress shared that she was not enchanted by Basanti initially.

"I was disappointed that after Seeta aur Geeta, Salim-Javed offered me the role of a tangewali. I had almost said no... but then director Ramesh Sippy, with whom I have had a long association, insisted that I do the film, I submitted. Today, everyone loves the character, but let me tell you that learning all those long lines and delivering them so fast was far from easy."

The director and the heroine were blissfully unaware of his pranks—and wondered why simple scenes were taking so long. Dharmendra confessed to these pranks recently in a television interview.

A Rare Example

In 50 years, many filmmakers have attempted remakes of the classic. Some as spoof, some as adventure, but nobody has dared to experiment with a different narrative. It would be irreverent I guess, but a thought often crosses my mind.

Indian cinema has always patronised the attraction of the opposites. One can think of innumerable films where a spirited girl is attracted to a quiet guy and the other way round.

(Bhawana Somaaya is a film journalist, critic, author, broadcaster and podcaster. She was bestowed with the prestigious Padma Shri by the President of India in 2017.)